|

The Film

The Captive Heart (Basil Dearden, 1946) The Captive Heart (Basil Dearden, 1946)

In the early years of the Second World War, a group of British prisoners of war are escorted to a camp. The disparate group includes long-time friends Ted (Jack Warner) and Dai (Mervyn Johns), who own a decorating business back home together; young Scotsman David (Gordon Jackson), who has been blinded in battle; devoutly middle-class Stephen, a musician; Major Dalrymple (Basil Radford), whose prewar career seems to have consisted of betting on horses – and being very good at it; Matthews (Jimmy Hanley), a former ‘wideboy’ and burglar; and Czechoslovakian concentration camp escapee Karel Hasek (Michael Redgrave), who has taken the identity of a dead British soldier, Captain Geoffrey Mitchell.

The lives within the camp of this group of captives are contrasted with the events occurring to their nearest and dearest back home, juxtaposed within the film’s visual narration and communicated to the POWs through letters from home: Dai’s wife Dilys (Rachel Thomas) falls pregnant with the couple’s daughter but sadly passes away during childbirth, and the child is raised in Dai’s absence by Ted’s wife; Stephen’s fiancée Caroline briefly rekindles her romance with former lover Robert (Robert Wyndham), and this is communicated to Stephen via a letter to him from Robert’s jilted fiancée; and David’s dedicated lover Elspeth (Margot Fitzsimmons) receives a letter from David, who is worried his permanent loss of sight will become a burden to the both of them, ending their relationship. Meanwhile, Hasek receives a letter from Mitchell’s alienated wife Celia (played Redgrave’s wife Rachel Kempson); he discovers that the real Mitchell was an unpleasant man, disliked by his immediate family. In order to continue his masquerade as Mitchell, thus avoiding the discovery by the Germans of his real identity as an escapee from a concentration camp, Hasek is forced to continue corresponding with Celia, and finds himself slowly falling in love with her.

The first picture Ealing made after the Second World War, Basil Dearden’s The Captive Heart (1946) conforms to the paradigms of Ealing’s other pictures about the war. Ealing’s war pictures, arguably more than their later comedies, have often been seen as exploring ‘the problem of the national community’ through their ‘incorporat[ion of] all classes and all regions in their vision of the war effort’ (Leach, 2004: 18). The Ealing war pictures usually ‘dealt with a group of men who must overcome their differences to ensure their own survival, as well as for the sake of the nation’ (ibid.). These differences are often based on class and regional identity. The first picture Ealing made after the Second World War, Basil Dearden’s The Captive Heart (1946) conforms to the paradigms of Ealing’s other pictures about the war. Ealing’s war pictures, arguably more than their later comedies, have often been seen as exploring ‘the problem of the national community’ through their ‘incorporat[ion of] all classes and all regions in their vision of the war effort’ (Leach, 2004: 18). The Ealing war pictures usually ‘dealt with a group of men who must overcome their differences to ensure their own survival, as well as for the sake of the nation’ (ibid.). These differences are often based on class and regional identity.

The Captive Heart explores this theme thoroughly, through the depiction of Captain Hasek and his relationship with the British POWs – all of whom represent different social classes, from the ‘wideboy’/burglar Matthews to the more resolutely bourgeois Dalrymple; and also represent different regions of the UK, from the Scottish David to the Welsh Dai. Initially, Captain Hasek is viewed with suspicion: owing to his fluent German, he is believed to be a ‘fifth columnist’. The audience, cognisant of Hasek’s theft of the dead Captain Mitchell’s clothes and identification papers, may also believe this to be true. (Though the casting of Michael Redgrave casts some doubt upon this interpretation, as does the film’s gradual revelation that the real Captain Mitchell is an unpleasant sort who is deeply disliked by his wife and children.) It takes some time before the true story is coaxed out of Mitchell, and even then the other POWs regard his tale – of escaping from a concentration camp – with suspicion, and their doubts about Hasek’s story may also resonate with the audience. However, as the narrative progresses Hasek becomes much more sympathetic, his version of events validated by his acceptance by Dalrymple, and his pleasant nature is thrown into relief by the film’s depiction of the real Mitchell’s unpleasant character.

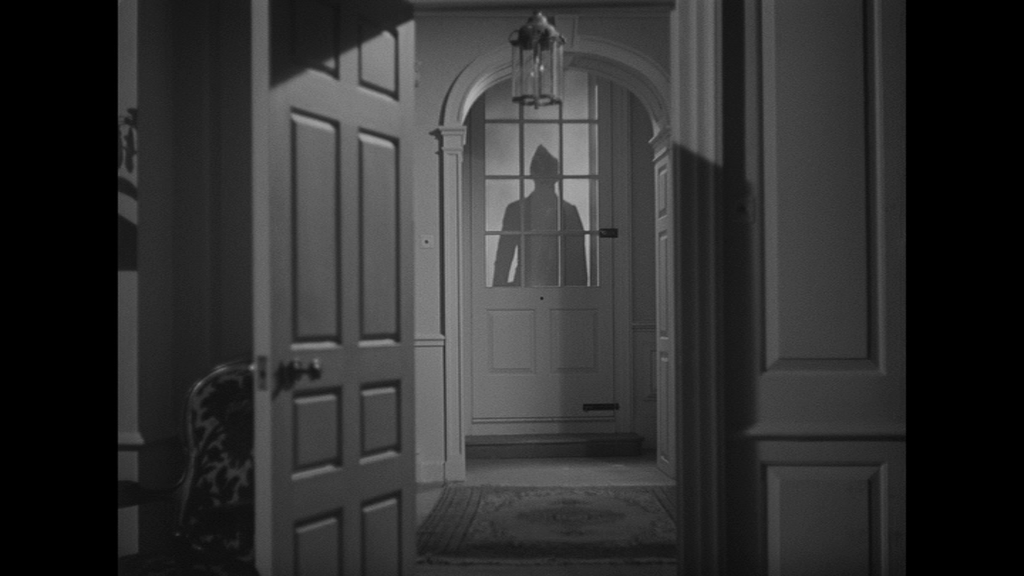

Throughout its running time, the film juxtaposes the lives of the men in the camp with the lives of their loved ones back home. This juxtaposition begins with the opening sequence, showing the men being forced to march to the prisoner of war camp. In the case of each soldier, we are presented with a close-up of their face which then dissolves to their memories of home: a close-up of Ted dissolves to a scene in his home, in the same room in which at the end of the film a repatriated Dai will meet his young daughter for the first time, where Ted and Dai joke with their wives prior to being sent to fight in France about their experiences with French girls during the First World War; a close-up of Stephen dissolves to his memories of the beginnings of his relationship with Caroline, who was the former lover of Stephen’s friend Robert; a close-up of David dissolves to his memories of saying goodbye to his family and his lover Elspeth. Finally, Hasek is given his flashback, to the moment when on the battlefield he stole the uniform and identity papers of the real Geoffrey Mitchell. This event forms the core of the narrative, Hasek’s identity as an outsider initially being regarded with suspicion by the British POWs but ultimately being the catalyst which pulls them together in order to protect Hasek.

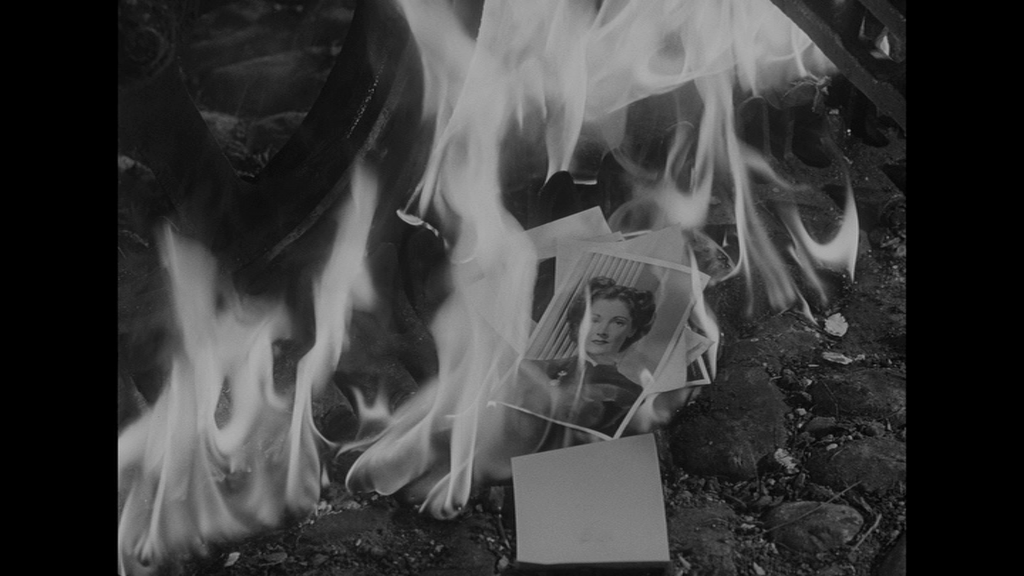

The death of the real Mitchell is followed shortly after by a flashback which reveals just how disliked he was by his family, a fact which makes Hasek’s adoption of Mitchell’s identity palatable. We see Celia, her father and her sons back home. ‘Will father ever come back to us, grandpa, even when the war’s over?’, one of Mitchell’s sons asks Celia’s father. ‘Well, would you be glad if he did?’, the boy’s grandfather asks in response. ‘No’, the boy says, ‘He used to make mummy cry’. Later, Celia discovers that Mitchell did not list her as his next of kin, an index of the lack of regard he felt for their marriage. Celia’s father tells her in reference to Mitchell, ‘Well, I for one don’t intend to shed any tears for him [….] I’m afraid that you may be carried away by sentimentality and suggest patching things up with him’. When, later in the film, Celia writes to Mitchell, Hasek realises that he must write back or else face the suspicion of the Germans, though he notes that ‘It’ll seem a pretty cruel fraud’ to reply to Celia. Hasek is told simply that ‘You’re wearing a dead man’s shoes. You’d better get used to reading them’. Realising that his handwriting will be recognised by Celia as not belonging to Mitchell, Hasek deliberately breaks his hand: as the men are driving posts into the ground, he slowly places his right hand on top of one of the posts where it is broken by the mallet that swings down upon it. Mitchell looks away as this happens, the sense of self-sacrifice underscored through a close-up of his face, which also reinforces the sense of repression/‘stiff-upper-lipness’ that makes Hasek an honorary Brit. The death of the real Mitchell is followed shortly after by a flashback which reveals just how disliked he was by his family, a fact which makes Hasek’s adoption of Mitchell’s identity palatable. We see Celia, her father and her sons back home. ‘Will father ever come back to us, grandpa, even when the war’s over?’, one of Mitchell’s sons asks Celia’s father. ‘Well, would you be glad if he did?’, the boy’s grandfather asks in response. ‘No’, the boy says, ‘He used to make mummy cry’. Later, Celia discovers that Mitchell did not list her as his next of kin, an index of the lack of regard he felt for their marriage. Celia’s father tells her in reference to Mitchell, ‘Well, I for one don’t intend to shed any tears for him [….] I’m afraid that you may be carried away by sentimentality and suggest patching things up with him’. When, later in the film, Celia writes to Mitchell, Hasek realises that he must write back or else face the suspicion of the Germans, though he notes that ‘It’ll seem a pretty cruel fraud’ to reply to Celia. Hasek is told simply that ‘You’re wearing a dead man’s shoes. You’d better get used to reading them’. Realising that his handwriting will be recognised by Celia as not belonging to Mitchell, Hasek deliberately breaks his hand: as the men are driving posts into the ground, he slowly places his right hand on top of one of the posts where it is broken by the mallet that swings down upon it. Mitchell looks away as this happens, the sense of self-sacrifice underscored through a close-up of his face, which also reinforces the sense of repression/‘stiff-upper-lipness’ that makes Hasek an honorary Brit.

The Captive Heart documents the occasional tensions within this group, but ultimately what shines through is the spirit of co-operation and support which the picture suggests is responsible for the ongoing survival of the men – their unbroken spirit – which is set against the Germans’ attempts to divide the men. This is expressed in the good humour of the POWs (‘Ain’t the Jerries that get me down’, one of the soldiers says as they march to the camp, ‘It’s them bloody cobbles.) Despite their initial differences, Ted and Dai offer Matthews, who is happy to brag about his pre-war experiences as a thief and swindler, a job. On their first meeting, Ted asks Matthews, ‘What’s your job in civvy street?’ ‘Only suckers work’, Matthews observes. ‘Oh, a wideboy, eh?’, Ted quips. In response to this, Dai says, ‘I’ll be home long before you two mugs are. I’m gonna scarper’. Later, when some of the men are to be repatriated and Hasek discovers his name (or rather, Mitchell’s) isn’t on the list, Matthews offers Mitchell his place; the plan is to break into the camp commandant’s office and adjust the list so that ‘Mitchell’ is to be repatriated and Matthews is to stay in the camp until the next round of repatriations take place. To achieve this, Matthews uses his skills as a burglar, putting his life at great risk and being attacked by a guard dog. The sense of the men’s comradeship forming an extended family is reinforced when Dai’s wife Dilys passes away during childbirth, and Flo raises the child until Dai can return home. When, having been repatriated, Ted and Dai return to Ted’s house, Dai finds his daughter happy and safe. Nevertheless, as the extradiegetic narrator at the start of the film tells us, and the men remind us in their dialogue, these captive soldiers remain the unsung heroes of the war – a wrong that in building a dramatic narrative around the plight of POW’s, The Captive Heart attempts to rectify. That opening narration describes the film as being ‘dedicated to prisoners of war. Their unbroken spirit is the symbol of a moral victory for which no bells are pealed and which will not be remembered’.

The civility and the sense of community amongst the POWs offsets the underhand tactics of their German captors. ‘Are your men afraid that this is some sort of propaganda trick’, a Gestapo officer asks Dalrymple after the men in the camp refuse to broadcast messages home over the radio. ‘Well, it’s just possible’, Dalrymple responds good-naturedly, in a moment of understatement. Towards the end of the film, Hasek receives a letter from Celia declaring how ‘normal’ life is within the idyllic village in which she lives, other than an influx of evacuee children. ‘And there’s still cricket on Saturdays’, her letter ends, and a shot of men playing cricket on the cricket pitch in the village cuts to a shot of the POWs playing cricket within the camp. This establishes visually the sense that the men within the camp have created within it a metonym of England. When Hasek accidentally reveals his masquerade as ‘Mitchell’ to the rest of the group (by saying he was attached to a machine gun company, which of course the British army did not have), some of the men suggest ‘string[ing] him up’. ‘Don’t let’s behave like a bunch of Nazis!’, one of the men shouts loudly, as if to undescore the differences between the British POWs and their German captors. When confronted directly, Mitchell reveals that is the son of the Czech ambassador to England and was previously a Professor of English at the University of Prague, and that he escaped from the camp after the Nazis killed his immediate family. The civility and the sense of community amongst the POWs offsets the underhand tactics of their German captors. ‘Are your men afraid that this is some sort of propaganda trick’, a Gestapo officer asks Dalrymple after the men in the camp refuse to broadcast messages home over the radio. ‘Well, it’s just possible’, Dalrymple responds good-naturedly, in a moment of understatement. Towards the end of the film, Hasek receives a letter from Celia declaring how ‘normal’ life is within the idyllic village in which she lives, other than an influx of evacuee children. ‘And there’s still cricket on Saturdays’, her letter ends, and a shot of men playing cricket on the cricket pitch in the village cuts to a shot of the POWs playing cricket within the camp. This establishes visually the sense that the men within the camp have created within it a metonym of England. When Hasek accidentally reveals his masquerade as ‘Mitchell’ to the rest of the group (by saying he was attached to a machine gun company, which of course the British army did not have), some of the men suggest ‘string[ing] him up’. ‘Don’t let’s behave like a bunch of Nazis!’, one of the men shouts loudly, as if to undescore the differences between the British POWs and their German captors. When confronted directly, Mitchell reveals that is the son of the Czech ambassador to England and was previously a Professor of English at the University of Prague, and that he escaped from the camp after the Nazis killed his immediate family.

Marcia Landy discusses The Captive Heart as one of a number of films which ‘addressed to the returned servicemen in their preoccupation with the psychic conflicts engendered by war and the return to civilian life’ (Landy, 1991: 173). For Landy, one of the film’s ‘major motifs […] is the need to adopt a more accepting view of non-British nationals’, something which is narrativised within the film’s examination of Hasek’s relationship with the British prisoners of war within the camp (ibid.). At the end of the film, Hasek has been ushered into a new life in England, and Landy describes the picture as ‘a conversion drama’ in which Hasek’s assumption of ‘a new identity and a new life’ is symbolic of the ‘“new man” who has emerged from the war’ (ibid.).

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. Based on a new restoration, it’s a crisp, clean presentation with the monochrome photography carried through nicely-balanced contrast levels with strongly-defined midtones: there’s a wonderful balance between light and dark within the photography which shines through in this presentation. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.37:1. Based on a new restoration, it’s a crisp, clean presentation with the monochrome photography carried through nicely-balanced contrast levels with strongly-defined midtones: there’s a wonderful balance between light and dark within the photography which shines through in this presentation.

The original cinema release of this film was cut by the BBFC in 1946. It’s unclear whether these cuts have persisted into subsequent home video releases. The film as presented here runs for 98:58 mins (PAL).

NB. Some larger screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel Dolby Digital mono track. This is clean and clear throughout, and dialogue is always audible. Optional English subtitles are included; there’s a slightly amusing error in the transcription of these subtitles, when Dalrymple speaks of a ‘chit’ in one specific sequence (45 minutes into the film), the subtitles erroneously transcribe the word as ‘shit’. Otherwise, the subtitles are accurate and easy to read.

Extras

The sole extra on this DVD release is an introduction by Charles Barr (6:50). Barr opens by apologising for his offhand dismissal of Dearden’s films in his famous book about Ealing Studios. Barr contextualises the film within a specific era of Ealing’s cinema, discussing some specific aspects of the film and its depiction of notions of England and English identity.

Overall

An entertaining film, The Captive Heart contains some wonderful moments of humour. Ted and Dai, veterans of the First World War, joke about the sense of repetition within the two conflicts: ‘It’s a shame we’ve got to close the business, Ted’, Dai says as the pair, in the opening flashback, prepare to leave for France. ‘Why?’, Ted quips, ‘It’s just a habit we’ve got into, fighting the same war every twenty years’. At times the dialogue becomes philosophical. Writing to Celia, Mitchell observes (in voiceover) that ‘It is not the duration but the indefiniteness of duration. For if a man knew the length of his sentence, he could plan accordingly’. Later, the doctor amongst the group notes, ‘Funny how much you learn about time when you’re killing it [….] I’ve got a theory that everything that counts is done by busy people. When you’ve got too little time, it’s extraordinary what you can do with it. And when you’ve got all the time in the world, like us, you don’t do a damn thing’. An entertaining film, The Captive Heart contains some wonderful moments of humour. Ted and Dai, veterans of the First World War, joke about the sense of repetition within the two conflicts: ‘It’s a shame we’ve got to close the business, Ted’, Dai says as the pair, in the opening flashback, prepare to leave for France. ‘Why?’, Ted quips, ‘It’s just a habit we’ve got into, fighting the same war every twenty years’. At times the dialogue becomes philosophical. Writing to Celia, Mitchell observes (in voiceover) that ‘It is not the duration but the indefiniteness of duration. For if a man knew the length of his sentence, he could plan accordingly’. Later, the doctor amongst the group notes, ‘Funny how much you learn about time when you’re killing it [….] I’ve got a theory that everything that counts is done by busy people. When you’ve got too little time, it’s extraordinary what you can do with it. And when you’ve got all the time in the world, like us, you don’t do a damn thing’.

The film’s focus on Hasek/‘Mitchell’ and his letters to Celia arguably overshadows some of the other stories within the picture, which are equally fascinating. Nevertheless, it’s a fascinating film, and the juxtaposition of life in the camp with life back home works very well.

This new DVD release contains a very good presentation of the film; it’s worth nothing that the restoration has also been released concurrently on Blu-ray.

References:

Landy, Marcia, 1991: British Genres – Cinema and Society, 1930-1960. Princeton University Press

Leach, Jim, 2004: British Film. Cambridge University Press

|