|

The Film

The Raging Moon (Bryan Forbes, 1971) The Raging Moon (Bryan Forbes, 1971)

Critically well-received in its day (Judith Crist suggested that Malcolm McDowell’s performance in the picture was one of the best screen performances of 1971), Bryan Forbes’ 1971 picture The Raging Moon has, for whatever reasons, disappeared into virtual obscurity (Crist, 1971: 54). The Raging Moon was based on Peter Marshall’s semi-autobiographical 1964 novel about the impact of polio on those afflicted by it. Marshall contracted polio at the age of eighteen and had previously written an autobiography, Two Lives (1963), whose title alluded to the difference between the life that Marshall lived before polio and his existence after it. Bryan Forbes’ film adaptation of Marshall’s novel follows its structure and tone quite closely, and in most respects could be regarded as a faithful and respectful adaptation of the source text. The film’s release, sadly, was not long before Marshall’s death in 1972 at the too-young age of thirty-three.

The film opens with an amateur football match, in which Bruce (Malcolm McDowell) is sent off by the referee after a confrontation. On the coach back, with his teammates and some young women who were spectators during the match, Bruce makes advances towards Edna, the girl next to whom he is sitting. However, he is quickly knocked back by her. Returning to his family home, where he lives with his parents (Patsy Smart and Jack Woolgar) and his brother Harold (Geoffrey Whitehead), Bruce is reminded of his brother’s impending marriage to Gladys (Theresa Watson).

At the wedding reception for Harold and Gladys, Bruce’s father and his uncle Bob come to blows over Bob’s incompetent work as the wedding’s photographer – using a Polaroid camera that Bob bought from a workmate. After the wedding reception, Bruce collapses in a life and wakes up in hospital. He has lost the use of his legs. At the wedding reception for Harold and Gladys, Bruce’s father and his uncle Bob come to blows over Bob’s incompetent work as the wedding’s photographer – using a Polaroid camera that Bob bought from a workmate. After the wedding reception, Bruce collapses in a life and wakes up in hospital. He has lost the use of his legs.

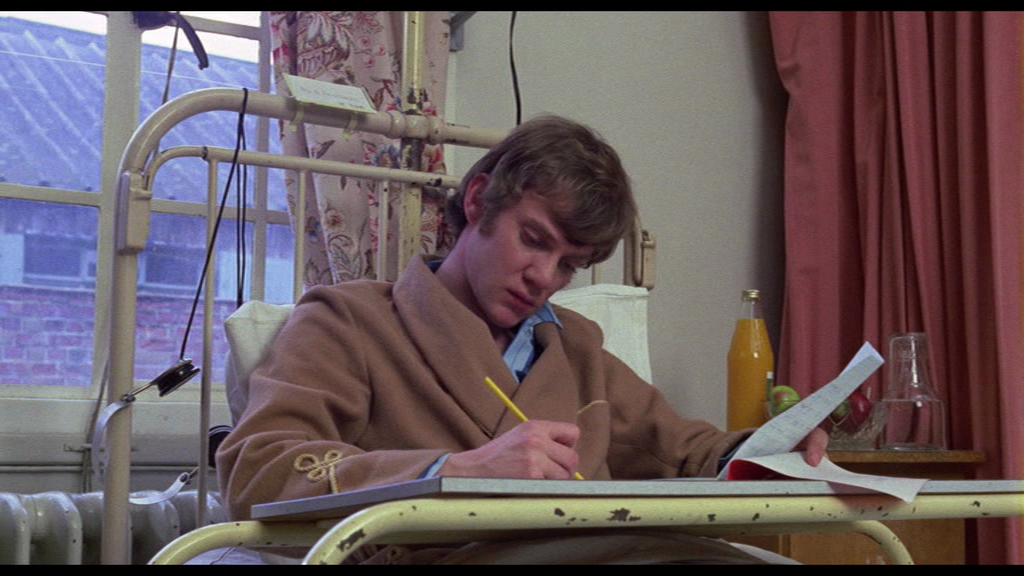

Whilst in the hospital, Bruce writes poetry. Insisting that ‘I don’t want to go home’, Bruce arranges to be transferred to a home for the disabled. The home is run by Reverend Carbett (Gerald Sim) and financed by the church. Bruce’s life in the home is miserable; he feels disconnected from the world around him. However, slowly he begins a relationship with Jill (Nanette Newman), a middle-class woman who is also a resident in the home. When first introduced to Bruce, Jill has a fiancé, Geoffrey, who shows little interest in her; however, Jill confronts Geoffrey, ending their relationship, before beginning a romance with Bruce.

The northern setting and the film’s opening focus on the sport of football, combined with Bruce’s combative behaviour, might remind the viewer of David Storey’s 1960 novel This Sporting Life, memorably adapted for the screen in 1963 by Lindsay Anderson, with Richard Harris in the role of rugby player Frank Machin. However, echoes of Storey’s novel are soon abandoned once Bruce finds himself in the hospital. Nevertheless, the low-key narrative and naturalistic photography and dialogue of The Raging Moon recall the approach of the British New Wave films of the late 1950s and early 1960s, with Bruce being depicted as something of an ‘angry young man’, his creative potential as a writer frustrated at the start of the film by his social class and, later in the picture, by his disability.

Early in the film, Bruce is introduced as a straight-talker, telling his parents that the football game from which he’s just returned had a referee that was ‘All piss and point’. To this, Bruce’s mother complains, ‘Oh, Bruce. Not on your brother’s wedding night’. ‘Well, he’s got to get used to life’s rich pageant, hasn’t he?’, Bruce quips in response. However, beneath his outwardly cocky façade, Bruce has an interior life that is more insecure: he presents himself as a worldly ladies’ man, but the reality is rather different. He makes advances to Edna on the bus back from the football match but she rebuts him. As the film starts, his brother Harold is getting married, something which Bruce finds hard to believe owing to Harold’s quiet manner and his naïvete about sex. At dinner with his family, Bruce jokes about Harold’s impending marriage: ‘You think she’ll turn up?’, he asks. However, alone with Harold in the bedroom they share, Bruce shows a much more compassionate side to his personality. Harold tells Bruce that he loves Gladys and ‘never thought I’d get married’. ‘Just so long as you don’t end up like them next door’, Bruce jokes whilst suggesting that Harold is lucky. (The irony of this is underscored by the sound, in the background, of Bruce and Harold’s parents arguing downstairs.) When Harold confesses that he’s a virgin, Bruce tells him kindly, ‘Well, you’re lucky. It’s [sex is] not that much. It’s not that much without love’; he’s utterly solemn in this moment, his comment signifying kindness towards his brother but also hinting at Bruce’s own profound sense of loneliness. Early in the film, Bruce is introduced as a straight-talker, telling his parents that the football game from which he’s just returned had a referee that was ‘All piss and point’. To this, Bruce’s mother complains, ‘Oh, Bruce. Not on your brother’s wedding night’. ‘Well, he’s got to get used to life’s rich pageant, hasn’t he?’, Bruce quips in response. However, beneath his outwardly cocky façade, Bruce has an interior life that is more insecure: he presents himself as a worldly ladies’ man, but the reality is rather different. He makes advances to Edna on the bus back from the football match but she rebuts him. As the film starts, his brother Harold is getting married, something which Bruce finds hard to believe owing to Harold’s quiet manner and his naïvete about sex. At dinner with his family, Bruce jokes about Harold’s impending marriage: ‘You think she’ll turn up?’, he asks. However, alone with Harold in the bedroom they share, Bruce shows a much more compassionate side to his personality. Harold tells Bruce that he loves Gladys and ‘never thought I’d get married’. ‘Just so long as you don’t end up like them next door’, Bruce jokes whilst suggesting that Harold is lucky. (The irony of this is underscored by the sound, in the background, of Bruce and Harold’s parents arguing downstairs.) When Harold confesses that he’s a virgin, Bruce tells him kindly, ‘Well, you’re lucky. It’s [sex is] not that much. It’s not that much without love’; he’s utterly solemn in this moment, his comment signifying kindness towards his brother but also hinting at Bruce’s own profound sense of loneliness.

Bruce’s sensitivity is reinforced at the wedding reception, where he witnesses his father and his uncle Bob come to blows over Bob’s poor photography of the event. In a scene which is almost a parody of the stereotypical representation of a northern wedding, the two drunken men fight and argue and then sit down with one another, laughing. Bruce watches before observing to his friend Terry, ‘Ah, they’ll be all right now. A little punch-up and a good cry’. He and Terry walk home together, and Bruce says to his friend, ‘Do you realise I’m 24 years old? Feel more like bloody 60’. Bruce’s words are meant as a gentle joke but have a ring of sadness about them. ‘Aye, you look bloody 60 as well’, Terry quips back. ‘My looks are the results of my efforts to become a great writer’, Bruce responds. Seeing that Bruce – though outwardly confident – is deeply morose, Terry offers to spend some time with Bruce, but Bruce turns his friend away: ‘I’m so all right, I wish to be alone’. Bruce enters the lift where he passes out – but not before experiencing a series of flashbacks, fragments of previous conversations phasing in and out on the audio track, accompanied by out-of-tune piano music. Bruce awakens in the hospital, where it is revealed that he has lost the use of his legs. ‘Doesn’t seem real, does it?’, says Terry. ‘Does if you’re lying here’, Bruce responds dryly. When a nurse dresses his bed for him, Bruce asks her to pinch his leg to see if the sensation has returned to it. He flirts with her, telling her, ‘I did feel something, you know’; but as the nurse walks away from the bed, Bruce adds – in reference to what he felt – ‘Bloody despair’.

As the film progresses, the relationships established earlier in the film gradually fade away, Bruce’s isolation being pushed front and centre. When Bruce is transferred from the hospital to the home, he sees no more of Terry, and even his close family seem not to visit him. For his family, Bruce comes to be defined by his illness. When, in the hospital prior to Bruce’s move to the home, Harold hesitates to tell Bruce about Gladys’ pregnancy, clearly conflicted about revealing his own good news to his brother within the current situation, Gladys chastises Harold: ‘Well, I feel sorry for him too’, she offers before adding cruelly that ‘we’ve got our life to think about now. His is over’. Discovering about Gladys’ pregnancy from Terry, Bruce lashes out at Harold: Has it kicked you out of bed yet? [….] The fruit of your loins? [….] That’s poetic. I just wrote that’, he says before noting sarcastically, ‘Helps you get a council house too, doesn’t it’. Bruce reacts to his family’s focus on his disability, telling them that ‘I’m not ill. You don’t say that. You don’t say “ill” to people like me [….] I’m not anything’. As the film progresses, the relationships established earlier in the film gradually fade away, Bruce’s isolation being pushed front and centre. When Bruce is transferred from the hospital to the home, he sees no more of Terry, and even his close family seem not to visit him. For his family, Bruce comes to be defined by his illness. When, in the hospital prior to Bruce’s move to the home, Harold hesitates to tell Bruce about Gladys’ pregnancy, clearly conflicted about revealing his own good news to his brother within the current situation, Gladys chastises Harold: ‘Well, I feel sorry for him too’, she offers before adding cruelly that ‘we’ve got our life to think about now. His is over’. Discovering about Gladys’ pregnancy from Terry, Bruce lashes out at Harold: Has it kicked you out of bed yet? [….] The fruit of your loins? [….] That’s poetic. I just wrote that’, he says before noting sarcastically, ‘Helps you get a council house too, doesn’t it’. Bruce reacts to his family’s focus on his disability, telling them that ‘I’m not ill. You don’t say that. You don’t say “ill” to people like me [….] I’m not anything’.

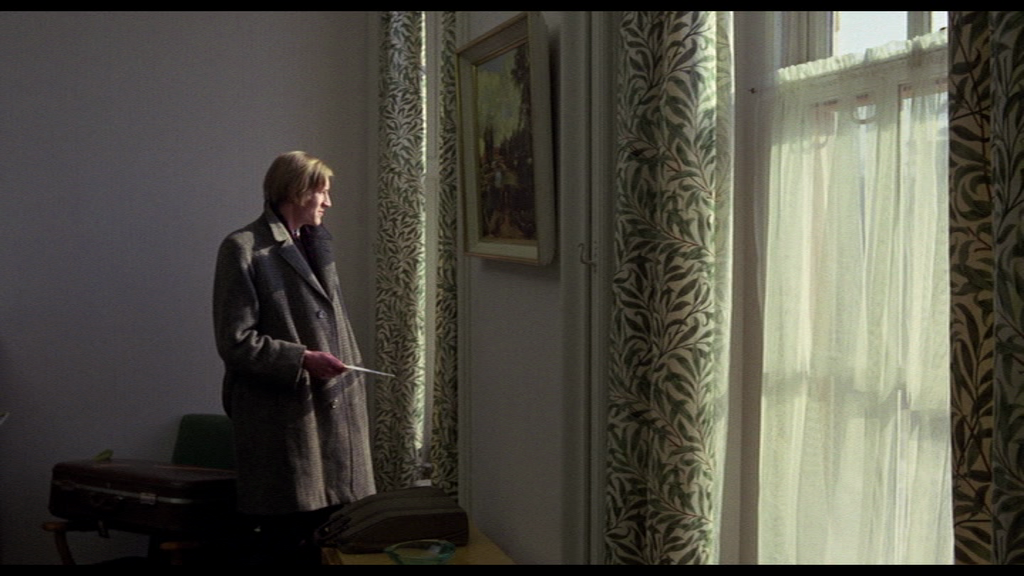

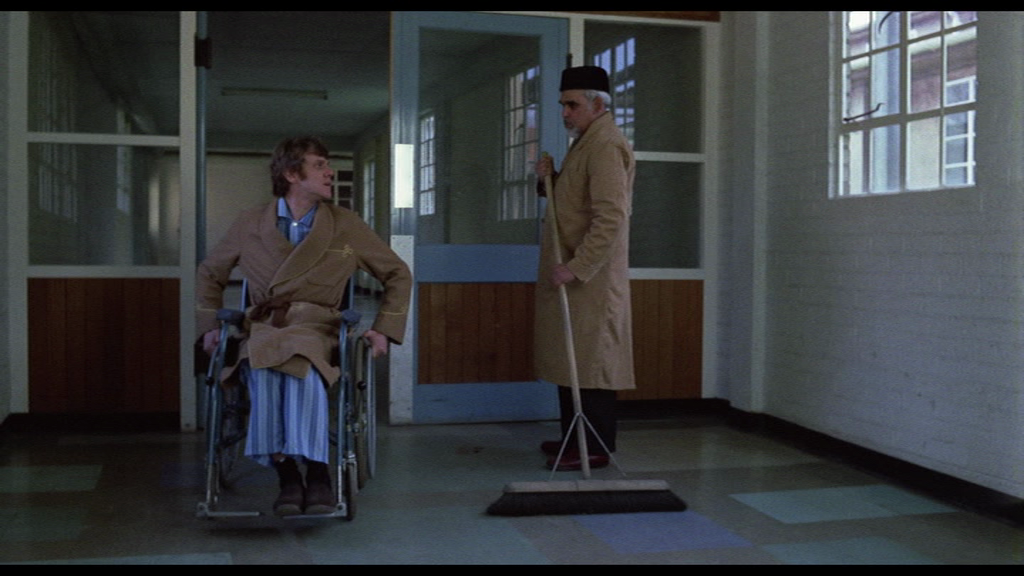

Within the home that Bruce is moved to, the residents are defined by their disabilities. This perspective is even reinforced through the residents’ attitudes towards one another, as if upon entering the home all hopes of living a ‘normal’ life of productivity in both relationships and work is abandoned. ‘Well, Bruce, what are you?’, Bruce is asked by another resident on his arrival. ‘What am I?’, Bruce asks, seemingly on the verge of telling the other resident that he’s a writer before being cut off by the question: ‘Are you polio?’ With her family, Jill faces the same prejudices and stereotypes as Bruce. When first introduced in the film, Jill has a fiancé who shows little interest in her and refuses to acknowledge her sexuality. To her father, Jill complains that ‘I’m a 31 year old crippled woman with a fiancé who’s looking for an out’. She confronts her fiancé, Geoffrey (Michael Lees), asking him if he ever thinks of her in a sexual way before reminding him that ‘I’m not deformed. It’s just my legs that don’t work’. Writing in Polio and Its Aftermath: The Paralysis of Culture, Marc Shell observes that in The Raging Moon Bruce and Jill ‘refuse to accept their families’ incomprehension and pity’ (Shell, 2005: 164). Overcoming the class differences that exist between them, Bruce and Jill find solace in one another’s company, against the prejudice exhibited by their family members and the film’s figures of authority. Meanwhile, later on, Bruce is approach by two of the older female residents, including Margaret (Nelly Hanham), who attempt to coax him into taking part in some activities, suggesting ‘You don’t want to be one of those, do you?’ When Bruce asks what ‘one of those’ means, Margaret indicates towards some of the other residents: ‘The vegetables’, she says, ‘The “kitchen gardens”, we call them. The people who just sit about, staring into space’.

The home itself is a culture shock for Bruce. As he arrives, with Harold in tow, Bruce sets his face into an expression of despairing resignation. He is told the strict rules of the establishment: ‘no perishable food in the rooms; no undue noise’. The sense of the home being like a prison camp is reinforced by the final dictate: the residents aren’t allowed off the site without permission. Despite this, completely unaware of the irony of her declaration, the matron who explains the rules of the home to Bruce tells him, ‘It’s all one big family’. Harold’s farewell to Bruce is awkward and stilted. Harold tries to talk to Bruce, but Bruce doesn’t speak a word. Harold says goodbye to his brother and kisses Bruce on the forehead. It’s a rare moment of intimacy and love in Bruce’s unhappy life, but there’s a finality to the moment as if this is the end of Bruch and Harold’s relationship. The home itself is a culture shock for Bruce. As he arrives, with Harold in tow, Bruce sets his face into an expression of despairing resignation. He is told the strict rules of the establishment: ‘no perishable food in the rooms; no undue noise’. The sense of the home being like a prison camp is reinforced by the final dictate: the residents aren’t allowed off the site without permission. Despite this, completely unaware of the irony of her declaration, the matron who explains the rules of the home to Bruce tells him, ‘It’s all one big family’. Harold’s farewell to Bruce is awkward and stilted. Harold tries to talk to Bruce, but Bruce doesn’t speak a word. Harold says goodbye to his brother and kisses Bruce on the forehead. It’s a rare moment of intimacy and love in Bruce’s unhappy life, but there’s a finality to the moment as if this is the end of Bruch and Harold’s relationship.

Bruce’s first meeting with Reverend Carbett, who runs the home, is awkward. ‘How do you think you’ll like being here?’, Carbett asks, a slightly patronising tone in his voice. ‘I’m not going to like being here at all’, Bruce replies. ‘Fair enough’, Carbett offers half-heartedly, ‘Life’s very difficult, I know. But I’m sure [….] if you give yourself a chance, you’ll get a lot of help and comfort from God’. Bruce reacts badly to this, mocking the vicar: ‘Tell me, if you buy your God, do you get a money back guarantee’, he asks before asking, ‘Well, I say, is He going to work the miracle?’ In response to this, Carbett offers platitudes, telling Bruce, ‘When I look at the state the world is in, I can see why so many young people reject religion. I don’t want you to think that I’m out of touch’.

The film begins with a quote from Dylan Thomas’ ‘In My Craft or Sullen Art’ (‘Not for the proud man apart / From the raging moon I write

On these spindrift pages / Nor for the towering dead / With their nightingales and psalms / But for the lovers, their arms / Round the griefs of the ages, / Who pay no praise or wages / Nor heed my craft or art’). The use of the poem, about the tension between writing for the sake of the craft as opposed to writing for material gain, establishes a theme explored later in the picture: that of Bruce’s aspirations as a writer. Bruce’s dedication to the craft of writing isn’t driven by a financial imperative, and several times he’s reminded of the difficulties he will face making a living as a writer – that writing isn’t a particularly well-paid job, and that he will struggle to pay his bills by practising that craft alone. When Bruce finally sells a story, he lies about its value to the matron of the home, telling her that he sold the story for £200. (Later, he reveals to Jill that he really sold it for £20, but wanted to teach the matron, who has been subtly mocking Bruce’s aspirations to write, a lesson.)

When he falls in love with Jill and the two plan to live together outside the home, Bruce seems satisfied with resigning his dream to become a professional writer, bowing to pressure and suggesting that instead, he will have to take up a ‘proper’ job in order to support both himself and Jill. Carbett tells Bruce that writing is ‘somewhat precarious sand to build your castle on’. Bruce reflects on this; to Jill, he says, ‘You know what I thought? I thought I could change the whole bloody world [….] But you know what, I think it changed me’. Shortly afterwards, he informs Jill that he plans to get ‘a real job’ in order to support them both. Ironically, whilst he is away at a job interview in preparation for this, Jill is rushed to hospital and dies – her death perhaps acting as a metaphor for the death of Bruce’s hopes and dreams of becoming a writer. Jill’s tragic death at the end of the film, ironically, frees Bruce to return to his writing – though the closing sequences suggest that it may be some time before Bruce realises this. (He returns to the home and, there, plays an aggressive game of table tennis with another of the residents – the batting back and forth of the ball symbolising the constant conflict within Bruce’s life.) When he falls in love with Jill and the two plan to live together outside the home, Bruce seems satisfied with resigning his dream to become a professional writer, bowing to pressure and suggesting that instead, he will have to take up a ‘proper’ job in order to support both himself and Jill. Carbett tells Bruce that writing is ‘somewhat precarious sand to build your castle on’. Bruce reflects on this; to Jill, he says, ‘You know what I thought? I thought I could change the whole bloody world [….] But you know what, I think it changed me’. Shortly afterwards, he informs Jill that he plans to get ‘a real job’ in order to support them both. Ironically, whilst he is away at a job interview in preparation for this, Jill is rushed to hospital and dies – her death perhaps acting as a metaphor for the death of Bruce’s hopes and dreams of becoming a writer. Jill’s tragic death at the end of the film, ironically, frees Bruce to return to his writing – though the closing sequences suggest that it may be some time before Bruce realises this. (He returns to the home and, there, plays an aggressive game of table tennis with another of the residents – the batting back and forth of the ball symbolising the constant conflict within Bruce’s life.)

It’s writing that reconnects Bruce to the world following his admittance to the home. After a period of adjustment, he begins to write alone in his room, using a typewriter. He makes friends of the home’s caretaker Bill (Barry Jackson) and Bill’s wife Sarah (Georgia Brown). The pair encourage Bruce’s writing. When Bruce asks Sarah if she will post a story for him, Sarah asks Bruce what he writes, asking if they are love stories. ‘Why should I write love stories?’, Bruce asks. Sarah reminds Bruce that even people in wheelchairs can fall in love.

The film was released in America as Long Ago, Tomorrow, where the picture’s opening titles were accompanied by a Burt Bacharach/Hal David-produced song sung by B J Thomas. This release is under the film’s original title, The Raging Moon, and is uncut – with a running time of 107:16 mins (PAL).

Video

The film has been scanned and restored in 2k from the original negative. In the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, with anamorphic enhancement, the presentation here is very good. The image is crisp and clear, with nicely balanced contrast levels and little to no discernible damage.

For larger screen grabs, please see the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via an English Dolby Digital 2.0 track, which is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The audio track is clear, and dialogue is audible throughout.

Extras

The disc includes two new interviews, with:

- Malcolm McDowell (19:39). McDowell talks about how he came to be involved in the film and reflect on its production. He comments on Shelagh Delaney’s contribution to the picture, and Bryan Forbes’ role in moving the project forwards. McDowell reveals that he researched the part at Stoke Newington hospital, discovering that most spinal injuries are owing to horse riding accidents or motorcycle accidents – something which put him off participating in either of those activities.

- Nanette Newman (18:26). Newman discusses the film’s production and reflects particularly on the film’s use of real locations. She also talks about the logistics of acting in a wheelchair.

Also included is a trailer (3:34) and a stills gallery.

Overall

In a uniformly positive review at the time of the film’s American release, Richard Schickel praised the integrity of the film’s approach to its subject and its overriding ‘honest sentiment’ which ‘makes you slightly ashamed of your feelings before the fact […] So well have we fortified ourselves against movies of this kind—especially after a tragedy like Love Story—that it is difficult to accept the simple truth: that writer-director Bryan Forbes has really brought it off’ (Schickel, 1971: 14). In a uniformly positive review at the time of the film’s American release, Richard Schickel praised the integrity of the film’s approach to its subject and its overriding ‘honest sentiment’ which ‘makes you slightly ashamed of your feelings before the fact […] So well have we fortified ourselves against movies of this kind—especially after a tragedy like Love Story—that it is difficult to accept the simple truth: that writer-director Bryan Forbes has really brought it off’ (Schickel, 1971: 14).

McDowell’s performance here is an interesting counterpoint to his role as Alex in Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, also made in 1971; and both pictures offer a depiction of youthful rebellion which contrasts with McDowell’s role in Lindsay Anderson’s If…. of a few years earlier (1968). Certainly, there’s a sense in which McDowell’s Bruce fits into the paradigms of the ‘angry young man’ of British New Wave cinema, and the opening sequence – with its depiction of a football match – suggests some similarities with This Sporting Life. However, as the narrative progresses, the film deviates from the expectations that such comparisons might set in place. It’s a warm, engaging picture, anchored by McDowell’s excellent performance.

Studiocanal’s new DVD release of the film contains a very good presentation of the main feature and two new interviews, with McDowell and Nanette Newman, which offer some fascinating insight into the production of the film. The release, and the film, come with a very high recommendation.

References:

Crist, Judith, 1971: ‘I’ve got a little list (and who doesn’t?)’ New York Magazine (17 January, 1972): 54-5

Schickel, Richard, 1971: ‘Love in an unlikely setting’. Life (5 November, 1971): 14

Shell, Marc, 2005: Polio and Its Aftermath: The Paralysis of Culture. Harvard University Press

|