|

|

The Film

Cosa avete fatto a Solange? AKA What Have You Done to Solange (Massimo Dallamano, 1972) Cosa avete fatto a Solange? AKA What Have You Done to Solange (Massimo Dallamano, 1972)

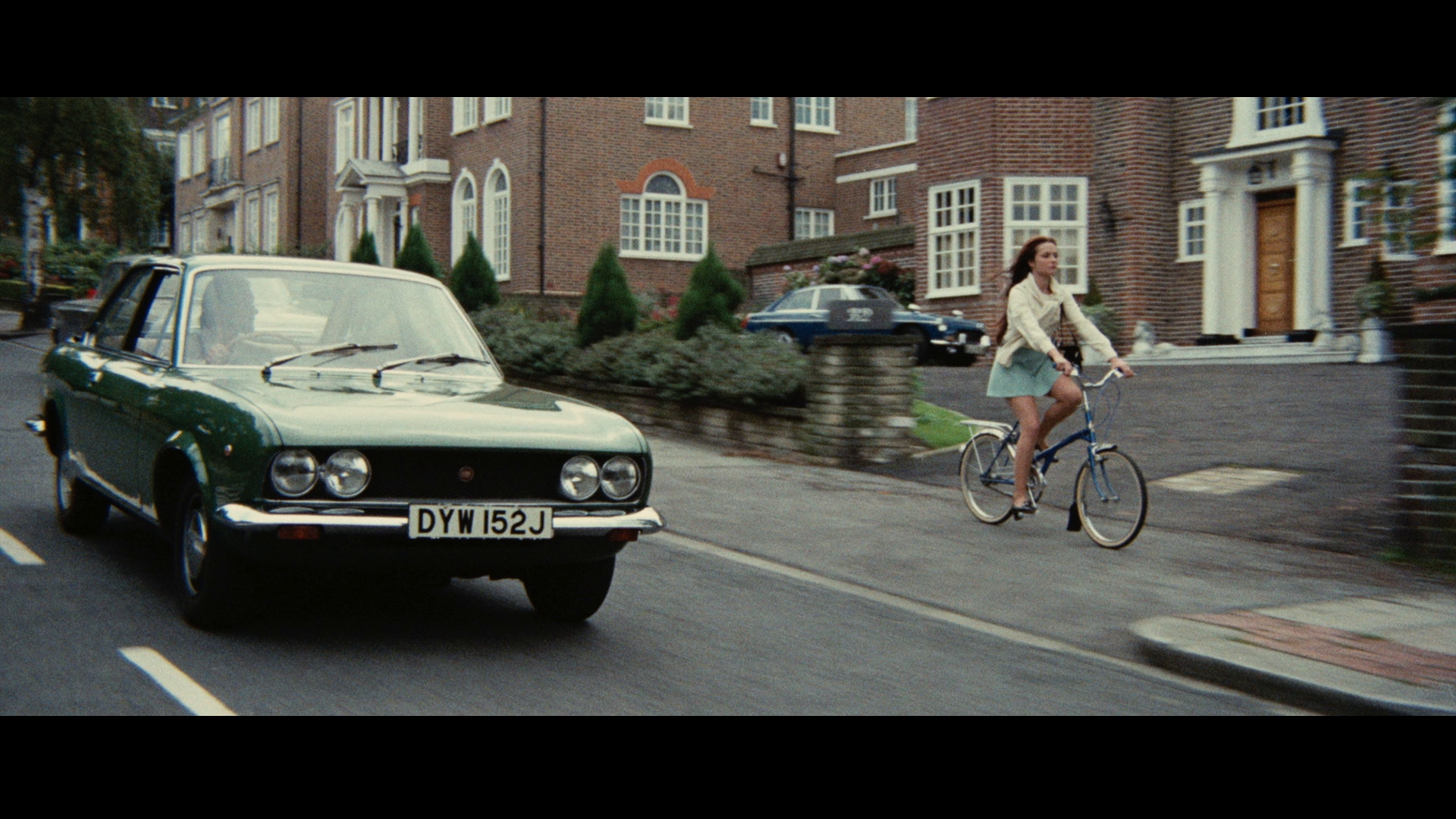

An icy combination of motifs from the thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) and the German Edgar Wallace krimi, Massimo Dallamano’s Cosa avete fatto a Solange? (What Have You Done to Solange?, 1972) was incredibly loosely based on Edgar Wallace’s 1920 novel The Clue of the New Pin. Dallamano’s film’s connection to the German krimi films was emphasised by the casting of two actors associated with that particular subgenre, Karin Baal and Joachim Fuchsberger; like many of the German Edgar Wallace adaptations, Cosa avete fatto a Solange? features a curiously off-kilter London setting, foregrounded in the film’s opening sequence by travelogue shots of London landmarks and a shot of a young boy riding an iconic London bus ‘ridealong’ in the street. Reflecting the picture’s status as a German-Italian coproduction, this London is populated by an international cast: Italian actor Fabio Testi takes the lead role, Enrico Rosseni, supported by the German actress Karin Baal as his character’s wife, Herta. Cosa avete fatto a Solange?’s German coproducers, Rialto Film, were one of the main producers of krimi pictures during the 1960s and into the 1970s, beginning with Harald Reinl’s Der Frosche mit der Maske (Face of the Frog, 1959), which also featured Joachim Fuchsberger in a lead role. (Fuchsberger plays the amateur sleuth Richard Gordon in Reinl’s picture, whereas in Solange he is promoted to the role of an official investigator, Detective Inspector Barth.) Colin Odell and Michelle LeBlanc note that by the early 1970s, near the end of the krimi cycle, Rialto Film’s productions ‘had become so similar to giallo [sic] they were being co-produced with Italy and even directed by Italians’ (Odell & LeBlanc, 2010: np). Odell and LeBlanc cite Solange and Umberto Lenzi’s Edgar Wallace adaptation Sette orchidee macchiate di rosso (Seven Blood-Stained Orchids, 1971), also coproduced by Rialto Film, as specific films which combine elements of the krimi with the paradigms of the thrilling all’italiana. Solange was followed by two films, with which Solange forms a loose ‘trilogy’ of pictures related by theme (the sexual exploitation and murder of schoolgirls) rather than narrative or character. Solange’s cross-pollenation of the krimi and the thrilling all’italiana also found its way into the second film in this series, Dallamano’s La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?/The Coed Murders, 1974), which marries the Italian thrilling with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police film). The final film in this loose ‘trilogy’, Alberto Negrin’s Enigma rosso (Red Rings of Fear/Rings of Fear/Trauma, 1978), is a more conventional thrilling picture, directed by Negrin from a script by Dallamano after Dallamano’s death in 1976.  In Solange, Enrico Rosseni (Fabio Testi), a teacher of Italian and physical education at a girls’ Catholic private school in London, is enjoying an illicit romantic liaision with one of his students, Elizabeth Eccles (Cristina Galbo). They lay together in a rowboat that floats idly on the Thames. However, to the consternation of Enrico, Elizabeth interrupts their canoodlings by asserting that she has seen something curious on the riverbank: a girl running in the distance, the flash of a blade and a man in a priest’s smock. Dropping Elizabeth off, Enrico returns to the home he shares with his wife Herta (Karin Baal). Herta, a German, is also a teacher at the school where Enrico works. The relationship between Enrico and Herta is cold and distant. Listening to the radio before leaving for work the next morning, Enrico hears a news broadcast which declares that the corpse of a young woman has been discovered on the riverbank. He visits the scene and watches the police investigation before travelling to work – where he excuses his tardiness by suggesting that his car broke down. In Solange, Enrico Rosseni (Fabio Testi), a teacher of Italian and physical education at a girls’ Catholic private school in London, is enjoying an illicit romantic liaision with one of his students, Elizabeth Eccles (Cristina Galbo). They lay together in a rowboat that floats idly on the Thames. However, to the consternation of Enrico, Elizabeth interrupts their canoodlings by asserting that she has seen something curious on the riverbank: a girl running in the distance, the flash of a blade and a man in a priest’s smock. Dropping Elizabeth off, Enrico returns to the home he shares with his wife Herta (Karin Baal). Herta, a German, is also a teacher at the school where Enrico works. The relationship between Enrico and Herta is cold and distant. Listening to the radio before leaving for work the next morning, Enrico hears a news broadcast which declares that the corpse of a young woman has been discovered on the riverbank. He visits the scene and watches the police investigation before travelling to work – where he excuses his tardiness by suggesting that his car broke down.

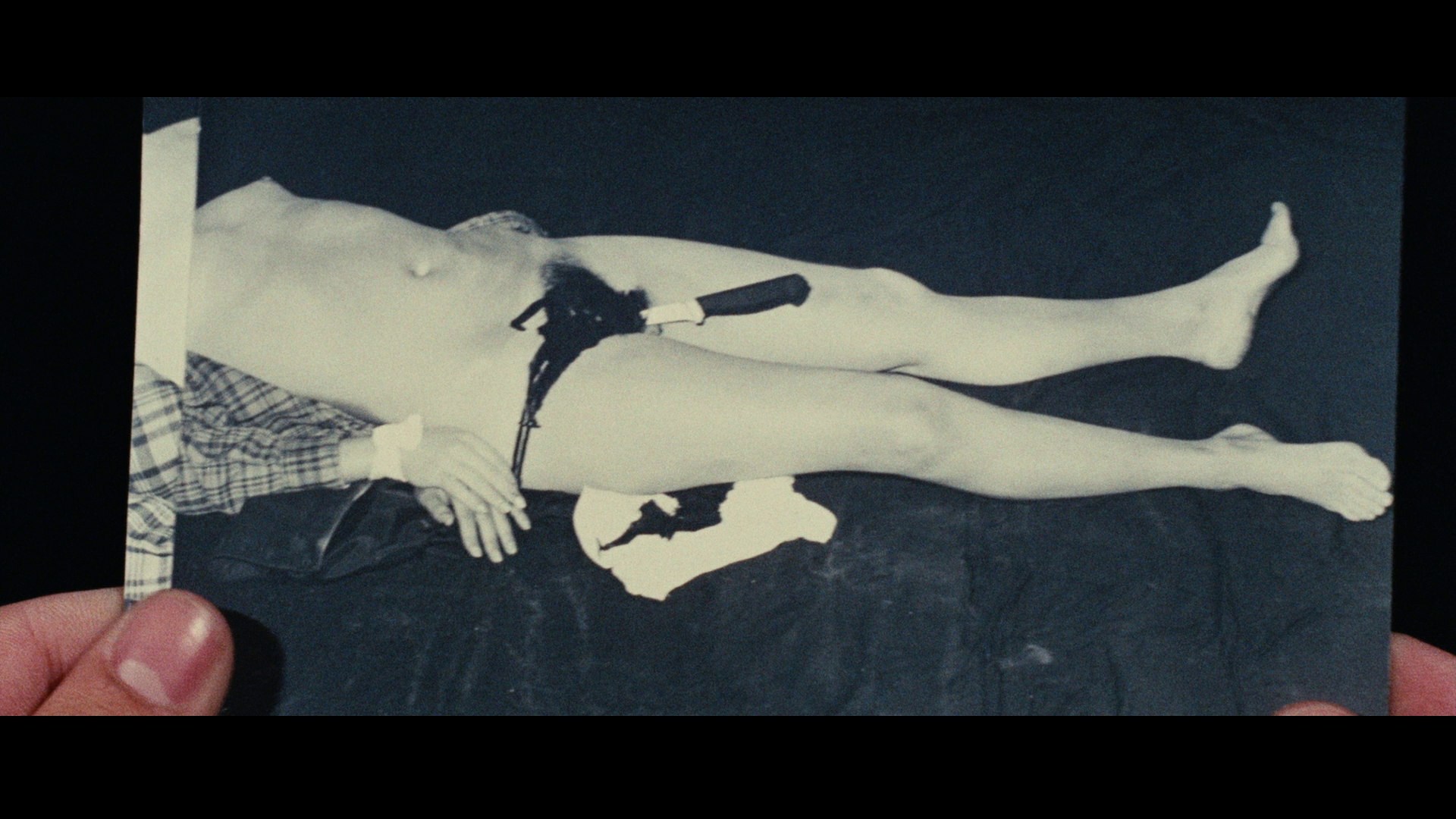

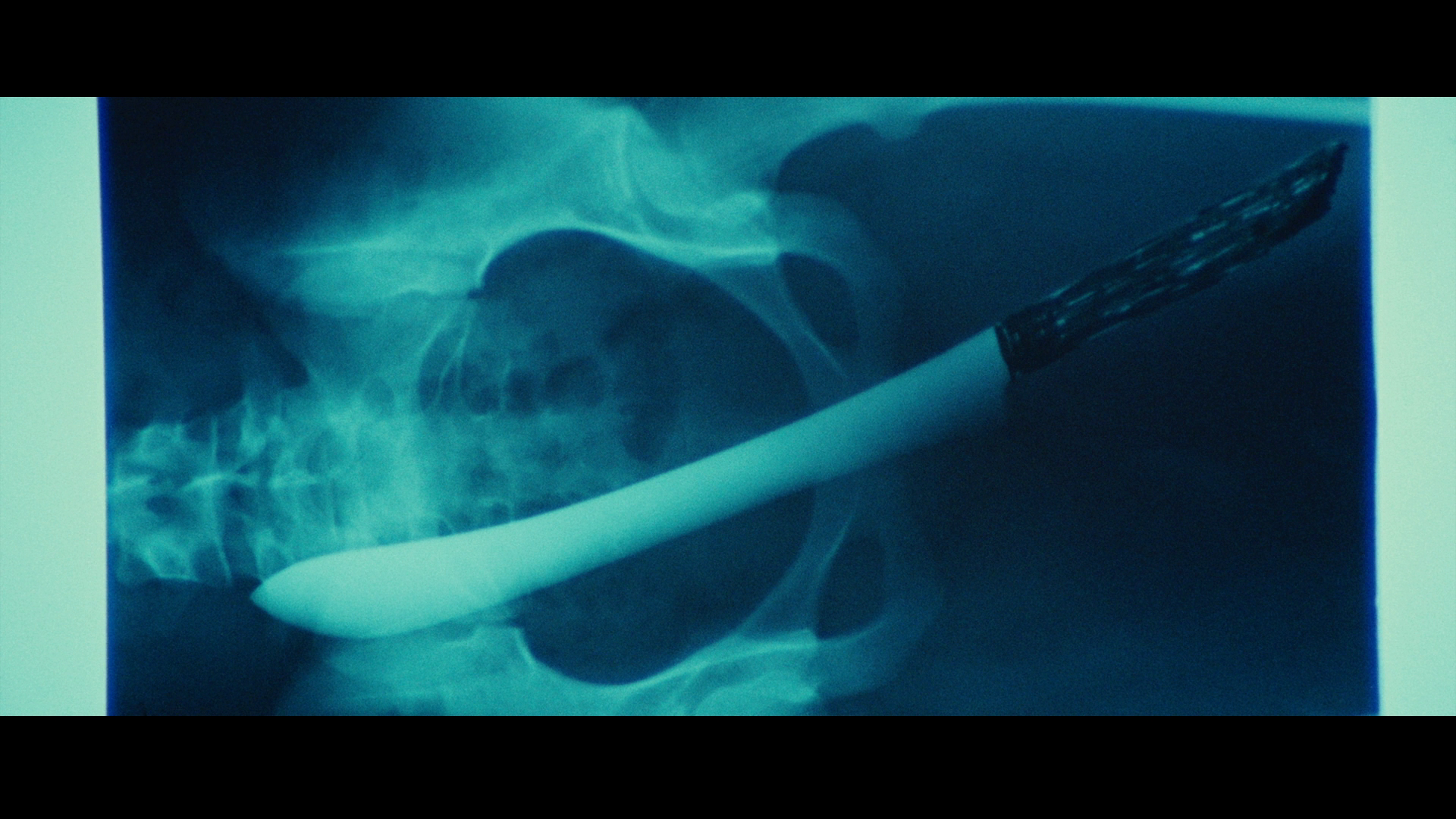

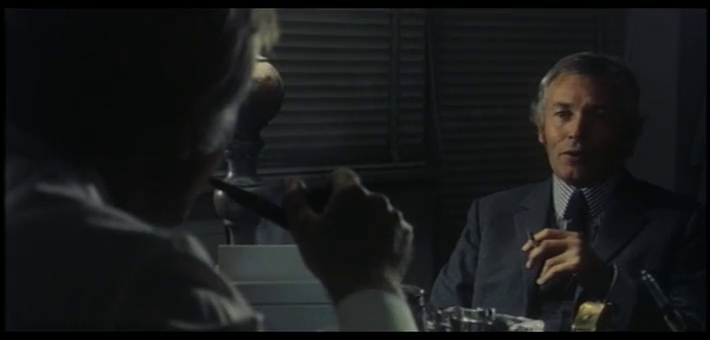

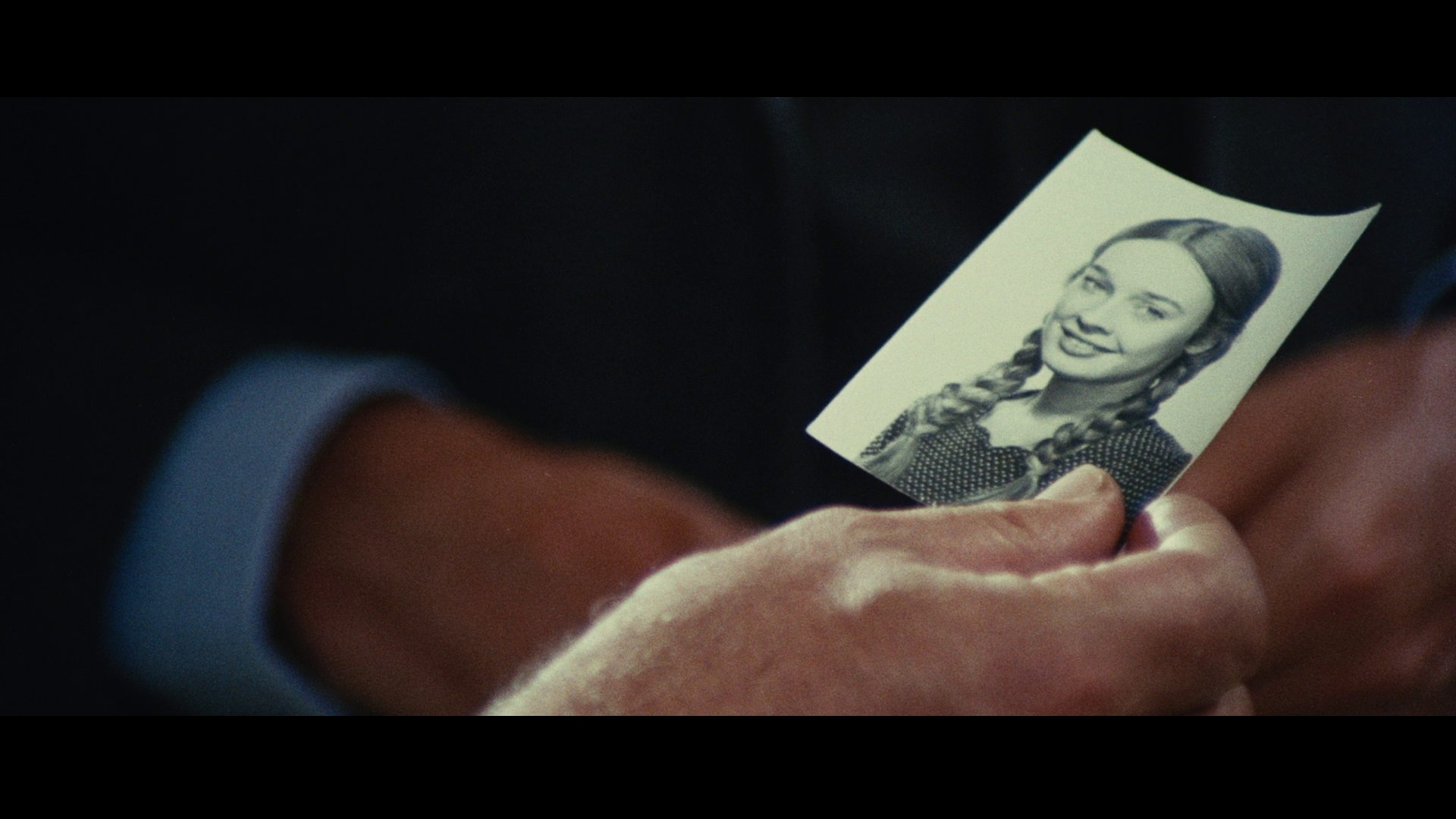

At the school, Enrico is introduced by the headteacher to Inspector Barth (Joachim Fuchsberger), who is investigating the murder: the victim was a student at the school. Barth shows the teaching staff photographs of the dead girl, Hilda Erickson, a long-bladed knife buried deep in her genitals. In the eyes of both Barth and Herta, Enrico is implicated by a photograph in the local newspaper which shows him standing at the crime scene on the morning that he arrived late for work. Eventually, Enrico confesses to Barth that he is involved in an affair with one of his students, and tells the detective what Elizabeth claims to have seen.  Enrico rents a flat with the intention of using it as a location for his secret liaisons with Elizabeth. However, whilst Elizabeth is alone in this flat she is attacked and killed by the same man who murdered Hilda. Elizabeth’s uncle, her guardian, is convinced that Enrico is the murderer, but the revelation that Elizabeth was a virgin when she died acts as a catalyst for the reconciliation between Enrico and Herta. Working together, husband and wife conduct their own amateur investigation into the case, hoping to identify the murderer of Elizabeth and the other girls. Their investigation leads to the revelation that Hilda and a group of other girls from the school have been taking part in sexual trysts with bohemian university students. The sexual experimentation of these young women met with harsh reality when one of their number, Solange Bureaugard (Camille Keaton), was forced to undergo a ‘backstreet’ abortion enacted by a local farmer, Ruth Holden (Emilia Wolkowich). This event in the recent past appears to have been the trigger for the murders that are taking place in the present. Enrico rents a flat with the intention of using it as a location for his secret liaisons with Elizabeth. However, whilst Elizabeth is alone in this flat she is attacked and killed by the same man who murdered Hilda. Elizabeth’s uncle, her guardian, is convinced that Enrico is the murderer, but the revelation that Elizabeth was a virgin when she died acts as a catalyst for the reconciliation between Enrico and Herta. Working together, husband and wife conduct their own amateur investigation into the case, hoping to identify the murderer of Elizabeth and the other girls. Their investigation leads to the revelation that Hilda and a group of other girls from the school have been taking part in sexual trysts with bohemian university students. The sexual experimentation of these young women met with harsh reality when one of their number, Solange Bureaugard (Camille Keaton), was forced to undergo a ‘backstreet’ abortion enacted by a local farmer, Ruth Holden (Emilia Wolkowich). This event in the recent past appears to have been the trigger for the murders that are taking place in the present.

Danny Shipka has suggested that Solange and La polizia chiede aiuto ‘are some of the most interesting and intense in the [thrilling] subgenre’, and that ‘taking a serious approach’ to the thrilling all’italiana, with Solange Dallamano delivers ‘[o]ne of the most satisfying gialli of its day’, with the film’s narrative combining ‘the right mount of sleaze and story to carry the audience through all the twists and turns with an emotionally satisfying ending’ (Shipka, 2011: 110). The elements of the thrilling all’italiana within the film most definitely follow the model for many early 1970s examples of the thrilling set by Dario Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970). Mikel J Koven cites this period of the thrilling, sulla stesso filone (in the tradition of) Dario Argento, as existing between 1970 and c.1975 (Koven, 2006: 6).  Solange, at least in its original version (the cut of the film released in Germany is substantially different), opens lyrically, with a seemingly idyllic scenario. In slow-motion, a group of young women ride their bicycles together, seemingly happy in one another’s company. Ennio Morricone’s score, which combines a soft piano refrain, accompanied by strings and woodwind instruments (swelling into a repeated leitmotif performed vocally by Edda Dell’Orso and accompanied by a guitar), suggests sweetness and serenity. This is undercut, however, by the use of a red filter: the colour suggests danger, violence and passion. As the film progresses, this idyllic scenario is undercut even further; the sense of idealism and sweetness within its depiction of youth (and, specifically, young femininity) is soured. As they investigate the murders and discover the secret society that the schoolgirls have formed, the principle characters express a cognisance of a deeply conservative idea: the notion that youth has been corrupted within the modern world of sexual freedom. Digging into the pasts of Elizabeth and the other girls, Enrico discovers the sordid reality of many of their lives, their nascent sexuality exploited by older boys, university students: ‘These girls know everything’, Enrico says to Herta at a late stage in the narrative, ‘They are sixteen and have a bunch of secret boyfriends, morbid jealousies, orgies, lesbian scenes. It wouldn’t surprise me to find out they used drugs’. The killer’s garb as a priest – specifically, a confessor – underscores this conservative worldview: ‘Why a priest?’, Enrico asks rhetorically before reasoning, ‘He confesses, absolves them, then kills them’. Later, one of the other teachers at the school declares that ‘Today, an eighteen year old girl is hardly a kid anymore. Even if it would be better if she were’. Gradually, the seemingly idyllic scene depicted within Solange’s opening moments is stripped of its joy, until at the end of the picture it is repeated, as part of an extended flashback, but this time in monochrome, stripped of the red filter through which it was presented in the opening sequence: the scene is revealed to be a depiction of the girls’ journey to Ruth Holden’s farm, where Solange Bureaugard would undergo the ‘backstreet’ abortion that would destroy her life and act as the catalyst for the series of murders around which the film’s main narrative revolves. Solange, at least in its original version (the cut of the film released in Germany is substantially different), opens lyrically, with a seemingly idyllic scenario. In slow-motion, a group of young women ride their bicycles together, seemingly happy in one another’s company. Ennio Morricone’s score, which combines a soft piano refrain, accompanied by strings and woodwind instruments (swelling into a repeated leitmotif performed vocally by Edda Dell’Orso and accompanied by a guitar), suggests sweetness and serenity. This is undercut, however, by the use of a red filter: the colour suggests danger, violence and passion. As the film progresses, this idyllic scenario is undercut even further; the sense of idealism and sweetness within its depiction of youth (and, specifically, young femininity) is soured. As they investigate the murders and discover the secret society that the schoolgirls have formed, the principle characters express a cognisance of a deeply conservative idea: the notion that youth has been corrupted within the modern world of sexual freedom. Digging into the pasts of Elizabeth and the other girls, Enrico discovers the sordid reality of many of their lives, their nascent sexuality exploited by older boys, university students: ‘These girls know everything’, Enrico says to Herta at a late stage in the narrative, ‘They are sixteen and have a bunch of secret boyfriends, morbid jealousies, orgies, lesbian scenes. It wouldn’t surprise me to find out they used drugs’. The killer’s garb as a priest – specifically, a confessor – underscores this conservative worldview: ‘Why a priest?’, Enrico asks rhetorically before reasoning, ‘He confesses, absolves them, then kills them’. Later, one of the other teachers at the school declares that ‘Today, an eighteen year old girl is hardly a kid anymore. Even if it would be better if she were’. Gradually, the seemingly idyllic scene depicted within Solange’s opening moments is stripped of its joy, until at the end of the picture it is repeated, as part of an extended flashback, but this time in monochrome, stripped of the red filter through which it was presented in the opening sequence: the scene is revealed to be a depiction of the girls’ journey to Ruth Holden’s farm, where Solange Bureaugard would undergo the ‘backstreet’ abortion that would destroy her life and act as the catalyst for the series of murders around which the film’s main narrative revolves.

In its focus on guilt, Catholicism and sexuality, Solange offers an off-kilter Italian take on English society. The London setting, tied to the film’s origins in Rialto Film’s past as a producer of Edgar Wallace krimi pictures, is simply a paradigmatic substitution: the picture’s narrative would make as much sense, if not more, in an Italian setting. The English setting of the film is anchored through the use of landmarks and recognisable iconography (the portraits of the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh that hang prominently in Barth’s office, for example). Today, the experience of viewing the film, with its elements of conspiracy and its askance look at schoolgirl sex rings in 1970s London, has a slightly more electrified charge owing to recent revelations – which admittedly, in most cases, aren’t so much ‘revelations’ as simply confirmations of long-standing rumours and speculation – about the curious peccadilloes of members of the British Establishment, both in the world of politics and the media, during the era in which the film was made. Enrico’s affair with Elizabeth is, within the narrative, resolved as ‘acceptable’ owing to the fact that her autopsy reveals that when she died, she was a virgin. In light of this, Herta is prepared not only to forgive her husband but to aid him in his search for Elizabeth’s murderer. (A modern viewer might be less inclined to let the character off the proverbial hook, however.)  Nevertheless, the film opens with an unsympathetic depiction of the character of Enrico. He and Elizabeth are laying in a rowboat on the Thames, their bodies fragmented by the shadows of the tree branches above them. Elizabeth turns Enrico down sexually, telling him ‘I desire it too, but not in this way’. Enrico tries to assuage her doubts with the empty promises of a man whose mind is set on an act of infidelity: ‘Soon I’ll settle everything’, he assures her, ‘You’ll see. It’s only a question of time’. Elizabeth soon interrupts their tryst, telling Enrico of what she has seen on the riverbank – later revealed to be the murder of one of her schoolmates, Hilda. ‘I’m not a good lover if you prefer watching the landscape’, Enrico grumbles, his pride hurt. His desire frustrated, Enrico chastises Elizabeth, suggesting that she is frigid and tainted by Catholic guilt about sex: ‘All because of the education you get in that school’, he moans, ‘They teach you only stupid things [….] There’s always something that stops you from being a normal girl’. He continues to mock Elizabeth, suggesting that her ‘vision’ is simply a symbol of the guilt she associates with her sexuality: ‘The Archangel Gabriel come to punish you for your sins’. For her part, Elizabeth protests meekly, ‘It really wasn’t a dream’. In this sequence, Enrico criticises the school as an agent of repression – obviously owing to his sexual frustration in the scenario with Elizabeth. Shortly afterwards, he becomes the voice of repression himself, telling Elizabeth to repress her desire to inform the police of what she believes she has seen. (‘Listen to me’, he insists, ‘We can’t always do what we would like to do’.) This is motivated, of course, by Enrico’s own instinct for self-preservation and his wish for his relationship with Elizabeth not to be made public. Nevertheless, the film opens with an unsympathetic depiction of the character of Enrico. He and Elizabeth are laying in a rowboat on the Thames, their bodies fragmented by the shadows of the tree branches above them. Elizabeth turns Enrico down sexually, telling him ‘I desire it too, but not in this way’. Enrico tries to assuage her doubts with the empty promises of a man whose mind is set on an act of infidelity: ‘Soon I’ll settle everything’, he assures her, ‘You’ll see. It’s only a question of time’. Elizabeth soon interrupts their tryst, telling Enrico of what she has seen on the riverbank – later revealed to be the murder of one of her schoolmates, Hilda. ‘I’m not a good lover if you prefer watching the landscape’, Enrico grumbles, his pride hurt. His desire frustrated, Enrico chastises Elizabeth, suggesting that she is frigid and tainted by Catholic guilt about sex: ‘All because of the education you get in that school’, he moans, ‘They teach you only stupid things [….] There’s always something that stops you from being a normal girl’. He continues to mock Elizabeth, suggesting that her ‘vision’ is simply a symbol of the guilt she associates with her sexuality: ‘The Archangel Gabriel come to punish you for your sins’. For her part, Elizabeth protests meekly, ‘It really wasn’t a dream’. In this sequence, Enrico criticises the school as an agent of repression – obviously owing to his sexual frustration in the scenario with Elizabeth. Shortly afterwards, he becomes the voice of repression himself, telling Elizabeth to repress her desire to inform the police of what she believes she has seen. (‘Listen to me’, he insists, ‘We can’t always do what we would like to do’.) This is motivated, of course, by Enrico’s own instinct for self-preservation and his wish for his relationship with Elizabeth not to be made public.

Throughout its narrative, Solange depicts young women who are controlled, manipulated and exploited by men who are agents of patriarchal institutions (private education, the church, the family). In some ways, despite its more overtly ‘sleazy’ content (the voyeuristic shots of the girls in the school’s communal shower, rendered deliriously ‘meta’ by the revelation that we are watching through the eyes of one of the male members of staff who has made a spyhole in the wall of the girls’ shower room), Solange may possibly be considered to be a crypto-feminist picture which focuses heavily on the ways in which young women are directed by the stereotypes ascribed to them by men. (Elizabeth seems aware of these stereotypes when, leaving her uncle’s home, she tells her uncle ‘I am not Little Red Riding Hood’, in allusion to the folk tale’s cautious moral fable about emergent female sexuality.) In terms of their relationships with the university students, the girls are shown as being exploited by these young men: interviewed by Enrico, one of the young men offers an offhand dismissal of Hilda and her friends, telling Enrico bitterly that ‘Even in bed, they [the girls] stick together. Those little dykes’. Richard Dyer notes that Solange’s prolonged flashback to Solange Beauregard’s abortion explicitly links ‘sexual experience [and experimentation] and the punishment for it’: when Solange asks Holden if the procedure will hurt, Holden replies ‘If it does, you’ve earned it’, and during the procedure Holden connects the abortion with the act of sex by telling Solange ‘Now do as you do when you make love, clench your teeth’ (Dyer, 2015: np). (Dyer argues that the abortion which forms the locus for the killer’s motive within the picture, and the implied lesbianism within the film, locates Solange within a group of examples of the thrilling all’italiana that depict abortion and homosexuality as ‘threatening’ elements of the sub/genre’s ‘fresco of corruption’; ibid.) Alberto Negrin’s Enigma rosso makes the ‘link between the horror of sex and that of abortion’ even more explicit, intercutting its abortion scene with a pivotal (and memorably unpleasant) murder of a young woman with a giant dildo (ibid.).  The film contrasts the archetypal frigid, sexless woman with the sexually liberated (and exploited) schoolgirls, filtering both of these through the perspective(s) of the male characters: Enrico, the other male teachers at the school, the university students with whom the girls have their trysts. For her part, Enrico’s wife Herta is initially presented as cold and distant, her relationship with Enrico devoid of any sexuality whatsoever. This is reinforced by the ‘buttoned-up’ appearance of Karin Baal in the film’s early sequences: she wears a very ‘rigid’, quite masculine suit and has her hair tightly pulled back. However, as the film progresses, and especially following the revelation that Elizabeth was a virgin when she was murdered, Herta acts more warmly towards Enrico and this is reflected in the appearance of the character too: she dresses in more stereotypically feminine fashions and wears her hair down. When Elizabeth’s uncle suggests that he is sure Enrico is the murderer, Herta protests and asserts that she is certain Enrico is innocent. Finally, whilst in Hyde Park, where Enrico unknowningly sees the mysterious Solange for the first time, they kiss; in this moment, photographed tenderly, their marriage is reasserted. The film contrasts the archetypal frigid, sexless woman with the sexually liberated (and exploited) schoolgirls, filtering both of these through the perspective(s) of the male characters: Enrico, the other male teachers at the school, the university students with whom the girls have their trysts. For her part, Enrico’s wife Herta is initially presented as cold and distant, her relationship with Enrico devoid of any sexuality whatsoever. This is reinforced by the ‘buttoned-up’ appearance of Karin Baal in the film’s early sequences: she wears a very ‘rigid’, quite masculine suit and has her hair tightly pulled back. However, as the film progresses, and especially following the revelation that Elizabeth was a virgin when she was murdered, Herta acts more warmly towards Enrico and this is reflected in the appearance of the character too: she dresses in more stereotypically feminine fashions and wears her hair down. When Elizabeth’s uncle suggests that he is sure Enrico is the murderer, Herta protests and asserts that she is certain Enrico is innocent. Finally, whilst in Hyde Park, where Enrico unknowningly sees the mysterious Solange for the first time, they kiss; in this moment, photographed tenderly, their marriage is reasserted.

The opening murder is depicted as a Freudian primal scene that haunts Elizabeth and, by extension, the narrative. At various moments throughout the film, Elizabeth returns again and again to the scene of the crime in her dialogue with Enrico, trying to recall the details within what she witnessed; the film, likewise, repeats this scene over and over again (in particular, the shot of the knifeblade flashing between Hilda’s thighs). (Many of the BBFC’s cuts to Redemption’s mid-1990s VHS release of the film were to these repeated flashbacks to the opening murder, the image of the knife between Hilda’s legs a particular point of contention – though the film, even in its uncut form, stops short of showing the actual act of penetration.) As in many other examples of the thrilling all’italiana – and specifically, those made sulla stesso filone Dario Argento – the witness of a violent crime struggles to recall the important details within the scenario. Elizabeth expresses her confusion about what she saw on the riverbank: ‘No, it as just a shadow. He was a dark shadow and he moved’, she tells Enrico, ‘I don’t know. I don’t know how to explain. I am sure it was a man, but there was something… strange’. Also in the vein of the sulla stessa filone Dario Argento, Solange features a protagonist – actually, dual protagonists, if one counts Enrico and Herta as a team – who is a cultural outsider: Enrico is an Italian living in London, and his wife Herta is German. There is cultural conflict between both Enrico and Herta and the English society in which they live, and between Enrico and Herta themselves. This is emphasised in a scene in which, to Herta, Enrico criticises the harshness of the German language, his wife’s mother tongue.  Shelley F O’Brien reminds us that ‘there are few examples of killer priests in films’, and that this is surprising ‘considering the horrific potential of this contradictory figure’ (O’Brien, 2011: 257). Most of the examples of films featuring killer priests, O’Brien suggests, are Italian examples of the thrilling all’italiana, which is perhaps to be expected considering how dominant Catholicism is within Italy and that most of the creative personnel involved in the production of these films had Catholic backgrounds (ibid.). In his discussion of pictures that focus on priests who are murderers, O’Brien highlights two examples of the thrilling all’italiana in particular: Antonio Bido’s Solamente nero (Bloodstained Shadow, 1978) and Lucio Fulci’s Non si sevizia un paperino (Don’t Torture a Duckling, 1972). On the other hand, O’Brien argues, there are a number of films from the same period which ‘on the surface appear to have priests as killers, but in fact they [the murderers] turn out to be impostors disguised as priests’ (ibid.). Solange is amongst this group, along with Pupi Avati’s La casa dalle finestre che ridono (The House with Laughing Windows, 1975) and Aldo Lado’s Chi l’ha vista morire? (Who Saw Her Die, 1976). O’Brien suggests that ‘the mere fact that the killers in these […] films choose to disguise themselves as priests in order to commit their crimes suggests something about the killer priest figure more generally’: in other words, that the inclusion of such a figure within a narrative ‘is often related to perceived immorality, the desire for retribution, and also as a device for misleading the audience’ (ibid.). Shelley F O’Brien reminds us that ‘there are few examples of killer priests in films’, and that this is surprising ‘considering the horrific potential of this contradictory figure’ (O’Brien, 2011: 257). Most of the examples of films featuring killer priests, O’Brien suggests, are Italian examples of the thrilling all’italiana, which is perhaps to be expected considering how dominant Catholicism is within Italy and that most of the creative personnel involved in the production of these films had Catholic backgrounds (ibid.). In his discussion of pictures that focus on priests who are murderers, O’Brien highlights two examples of the thrilling all’italiana in particular: Antonio Bido’s Solamente nero (Bloodstained Shadow, 1978) and Lucio Fulci’s Non si sevizia un paperino (Don’t Torture a Duckling, 1972). On the other hand, O’Brien argues, there are a number of films from the same period which ‘on the surface appear to have priests as killers, but in fact they [the murderers] turn out to be impostors disguised as priests’ (ibid.). Solange is amongst this group, along with Pupi Avati’s La casa dalle finestre che ridono (The House with Laughing Windows, 1975) and Aldo Lado’s Chi l’ha vista morire? (Who Saw Her Die, 1976). O’Brien suggests that ‘the mere fact that the killers in these […] films choose to disguise themselves as priests in order to commit their crimes suggests something about the killer priest figure more generally’: in other words, that the inclusion of such a figure within a narrative ‘is often related to perceived immorality, the desire for retribution, and also as a device for misleading the audience’ (ibid.).

A ‘localised’ version of Solange, released in West Germany under the title Das Geheimnis der grünen Stecknadel, highlighted the film’s Edgar Wallace connection, and in particular its association with Rialto Film’s other krimi pictures, by recutting the opening sequence to feature the first murder as part of a precredits scene (a paradigm of Rialto’s krimis) and including the series’ iconic gunshots – accompanied onscreen by splotches of red intended to metonymically represent bullet holes in a cadaver – over the opening titles, followed by the offscreen declaration ‘Hallo, hier spricht Edgar Wallace’ (‘Hello, this is Edgar Wallace speaking’). This version of the film cut many of the more overtly ‘sleazy’ sequences, reducing the running time by around ten minutes, and had the effect of foregrounding the character of Barth, played by Fuchsberger. Meanwhile, in Britain, the country in which the film is of course set, Solange was refused a certificate when originally submitted for classification in 1973 (under the title Solange); in the mid-1990s, the BBFC finally passed Solange for home video release by Redemption, but demanded cuts of 2:15 minutes, predominantly to the film’s sequences of murder. Cuts were to the ‘primal scene’ in the opening sequence (Elizabeth’s witnessing of her schoolmate’s death by a large knife being thrust into her groin, which is re-presented throughout the film via moments of analepsis/flashbacks, all of which were cut by the BBFC), the drowning of Elizabeth in the bathtub, Enrico’s discovery of Ruth Holden’s corpse (which has a sickle symbolically buried in Holden’s groin), and the extended analepsis at the end of the film to Solange’s abortion at the hands of Holden. Arrow’s new Blu-ray represents Solange’s first uncut release in the UK, with a running time of 106:43 mins.

Video

On startup, the viewer is presented with the option of watching the film in its English or Italian version – in other words, with onscreen text and dialogue in either English or Italian (with optional English subtitles). Taking up approximately 29Gb of space on a dual-layered disc, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is exhibited in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. Photographed by Aristide Massaccessi in Techniscope, Solange demonstrates the characteristics of films shot in that format. A cost-saving 2-perf format, Techniscope achieved a widescreen ratio of approximately 2.35:1 without the use of anamorphic lenses. This decreased production costs by halving the amount of film stock used and reducing the need to hire expensive anamorphic lenses, though it is said that the lab costs of films shot in Techniscope were higher than those of films shot using more conventional anamorphic widescreen processes. (The increasing lab costs were one of the reasons why Techniscope became increasingly less popular during the late-1970s.) On startup, the viewer is presented with the option of watching the film in its English or Italian version – in other words, with onscreen text and dialogue in either English or Italian (with optional English subtitles). Taking up approximately 29Gb of space on a dual-layered disc, the 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec, and the film is exhibited in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. Photographed by Aristide Massaccessi in Techniscope, Solange demonstrates the characteristics of films shot in that format. A cost-saving 2-perf format, Techniscope achieved a widescreen ratio of approximately 2.35:1 without the use of anamorphic lenses. This decreased production costs by halving the amount of film stock used and reducing the need to hire expensive anamorphic lenses, though it is said that the lab costs of films shot in Techniscope were higher than those of films shot using more conventional anamorphic widescreen processes. (The increasing lab costs were one of the reasons why Techniscope became increasingly less popular during the late-1970s.)

Release prints of Techniscope pictures were made by anthropomorphising the image and doubling the size of each frame, resulting in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of widescreen films shot using anamorphic lenses. (This was compounded in many 1970s Techniscope productions by the movement away from the dye transfer processes used by Technicolor Italia during the 1960s and towards the use of the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative, with the additional ‘generation’ of the material making the grain structure of the release prints of Techniscope productions during the 1970s more coarse and the blacks less rich.) Another of the characteristics of Techniscope photography was an increased depth of field. Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances, thus achieving a greater depth of field, even at lower f-stops and even within low light sequences. By effectively halving the ‘circle of confusion’, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and altered the field of view associated with them – so an 18mm lens would function pretty much as a 35mm lens, and shooting at f2.8 would result in similar depth of field to shooting at f5.6. The use of shorter focal lengths also prevented the subtle flattening of perspective that comes with the use of focal lengths above around 85mm. (The noticeably increased depth of field, combined with short focal lengths/wide-angle lenses, is a characteristic of many films shot in Techniscope, including Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964.)  This presentation is based upon a new 2k restoration from Solange’s original negative, thus bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage and resulting in an image that looks more like a Techniscope print produced by Technicolor Italia’s dye transfer process than the release prints of many 1970s Techniscope productions; thus the presentation here has a finer grain structure than some print-sourced (or IP-sourced) presentations of roughly contemporaneous Techniscope pictures. Contrast seems noticeably more bold than previous DVD presentations of Solange but appears balanced and even and more filmlike because of this. Photographed by Aristide Massaccessi (who also directed films under the more well-known Anglicised name ‘Joe D’Amato’), Solange makes notable use of wide-angle lenses in a number of sequences, especially those set in the school and the church. The photography features strong depth of field throughout, with many scenes staged in depth – a face in close-up in the foreground and action taking place in the background, for example. Colours are vibrant and deep, as can be seen from the red tint of the opening titles sequence – the deep red being vibrant and deep here. The presentation has the structure of 35mm film, carried by a strong encode to disc. This presentation is based upon a new 2k restoration from Solange’s original negative, thus bypassing the 4-perf blow-up stage and resulting in an image that looks more like a Techniscope print produced by Technicolor Italia’s dye transfer process than the release prints of many 1970s Techniscope productions; thus the presentation here has a finer grain structure than some print-sourced (or IP-sourced) presentations of roughly contemporaneous Techniscope pictures. Contrast seems noticeably more bold than previous DVD presentations of Solange but appears balanced and even and more filmlike because of this. Photographed by Aristide Massaccessi (who also directed films under the more well-known Anglicised name ‘Joe D’Amato’), Solange makes notable use of wide-angle lenses in a number of sequences, especially those set in the school and the church. The photography features strong depth of field throughout, with many scenes staged in depth – a face in close-up in the foreground and action taking place in the background, for example. Colours are vibrant and deep, as can be seen from the red tint of the opening titles sequence – the deep red being vibrant and deep here. The presentation has the structure of 35mm film, carried by a strong encode to disc.

NB. Some larger screengrabs are included below, along with some comparison grabs from the old EC Entertainment DVD release, the film’s first digital home video release. As can be seen from these grabs, aside from the obvious improvements in terms of contrast, detail and colour reproduction, Arrow’s release opens up the framing in comparison with the EC disc. (EC Entertainment’s release was also a clumsy PAL-NTSC transfer.) The film has also been released on DVD in the mid-2000s by Shriek Show in the US; that release was an improvement over the EC Entertainment disc but was interlaced. The best of the film’s previous DVD releases was the release from Italy’s 01 Distribution, though Arrow’s new Blu-ray release easily trumps that presentation of Solange.

Audio

The disc contains both the English and Italian language versions of the film, with both audio tracks presented in DTS-HD MA 1.0 mono.  The film’s narrative takes place in London, but it’s a strange, abstract and almost dreamlike version of London filtered through Italian Catholic sensibilities and anchored geographically by bizarre stereotypes: Barth, for example, has in his office portraits of the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh, which the photography is careful to emphasise in every scene that takes place in that location. (This is in stark contrast to roughly contemporaneous homegrown stories about detectives, such as Euston Films’ television series The Sweeney, 1974-8.) Given this, the English track might be taken as preferable. Though the film was post-synced, like many Italian films of the era, it seems that for some of the actors at least (Fuchsberger, for example – a fact confirmed in the interview with Baal that’s included on this disc), the dialogue in the English version matches their lip movements. Testi’s character speaks in heavily accented English throughout, reminding the viewer of this heritage as a ‘foreigner’, which is an element reinforced by the film’s narrative. That said, the Italian dialogue seems to have a more natural sense of rhythm and flow. The content of the dialogue in both versions of the film is pretty much the same, however. For example, in the English-language version of the film, Inspector Barth is told by the school’s headteacher that ‘Now, we are all here, inspector. All the professors of the upper form, including the teacher of gymnastics’; in the Italian-language version, the headteacher declares that ‘we are all here, inspector. All the second year teachers. They are all here, including the gym teacher’. Curiously, in the English version Herta’s profession is given as the teacher of ‘music and German’, whereas in the Italian version of the picture Herta is presented as the school’s ‘teacher of mathematics’. The film’s narrative takes place in London, but it’s a strange, abstract and almost dreamlike version of London filtered through Italian Catholic sensibilities and anchored geographically by bizarre stereotypes: Barth, for example, has in his office portraits of the Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh, which the photography is careful to emphasise in every scene that takes place in that location. (This is in stark contrast to roughly contemporaneous homegrown stories about detectives, such as Euston Films’ television series The Sweeney, 1974-8.) Given this, the English track might be taken as preferable. Though the film was post-synced, like many Italian films of the era, it seems that for some of the actors at least (Fuchsberger, for example – a fact confirmed in the interview with Baal that’s included on this disc), the dialogue in the English version matches their lip movements. Testi’s character speaks in heavily accented English throughout, reminding the viewer of this heritage as a ‘foreigner’, which is an element reinforced by the film’s narrative. That said, the Italian dialogue seems to have a more natural sense of rhythm and flow. The content of the dialogue in both versions of the film is pretty much the same, however. For example, in the English-language version of the film, Inspector Barth is told by the school’s headteacher that ‘Now, we are all here, inspector. All the professors of the upper form, including the teacher of gymnastics’; in the Italian-language version, the headteacher declares that ‘we are all here, inspector. All the second year teachers. They are all here, including the gym teacher’. Curiously, in the English version Herta’s profession is given as the teacher of ‘music and German’, whereas in the Italian version of the picture Herta is presented as the school’s ‘teacher of mathematics’.

Both tracks demonstrate strong range, which can be heard in the film’s use of Morricone’s score during its opening sequences. However, the English track is a little more bassy and a little less rich and full-bodied, with a slightly ‘tinny’ and ‘hollow’ sound to it. The Italian track is warmer and more rounded. The Italian track is accompanied by optional English subtitles, and the English track is also presented with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The subtitles are clear, free of grammatical errors and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes a good array of contextual material; it features: The disc includes a good array of contextual material; it features:

- an audio commentary with Kim Newman and Alan Jones. Newman admits that Jones is the real expert here, and Newman is present on the track to act as a foil for Jones and function essentially as a moderator. They talk about the picture’s reputation and Dallamano’s career generally. They reflect on Solange’s appeal, with Jones suggesting that the picture is ‘an anti-giallo in a way’, subverting some of the characteristics of other Italian thrillers of the period. The track is lively and informative, and as ever Newman and Jones are engaging and easy to listen to. - a newly-filmed interview with Karin Baal (13:38), and newly-edited interviews with Fabio Testi (21:17) and the film’s producer Fulvio Lucisano (11:03). The latter two interviews were shot in 2006, whereas the interview with Baal is utterly new. In his interview, Testi discusses the popularity of Italian films during the 1970s and his transition from working as a stuntman to working as a leading actor. He talks about the ways in which Italian filmmaking was ‘in the hands of the left’ and funding to it was cut post-1972 by a government who was cognisant, and wary, of the Italian film industry’s areas of political bias. He also discusses his relationship with the films he made during that era, suggesting that if he were to make some of those films today, he would approach his work as an actor differently. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. Lucisano talks about his working relationship with Dallama no and Solange’s status as an international coproduction. He reflects on Dallamano’s past as a cinematographer, which Lucisano suggests made Dallamano an extremely efficient director. He discusses the production of Solange and contrasts the ways in which filmmaking was approached in the 1970s with today. He also talks about Massaccessi’s work on Solange as the film’s cinematographer, and Morricone’s score for the picture. The film’s censorship history is also examined, and Lucisano suggests that ‘the film is against abortion, as far as I’m concerned’, but nevertheless the sequence depicting Solange’s abortion proved particularly controversial in Italy. This interview is again in Italian, with optional English subtitles.  Baal talks about how she came to be involved in Solange. Her initial response to the script was to tell Dallamano that the picture ‘could easily be made into a porn movie’, so she amended her contract to assert that she will not appear naked in the film and will not be associated with any of the pornographic scenes; she was convinced to make the picture owing to Fuchsberger’s involvement, and came to realise that the picture ‘wasn’t exactly porn, but it was so squalid’. The film ‘is set in a school where the teachers look like pickpockets and small-time crooks’, Baal asserts, highlighting in particular the sequence in which one of the teachers spies on the girls in the communal shower and ‘All you could see were black triangles and tits, no faces’. Baal is heavily critical, as is suggested from these comments, about the ‘sleazy’ aspects of the picture. She reveals that Fuchsberger shot his lines in English, whilst many of the other actors spoke their own languages on set. Testi, Baal suggests, ‘didn’t learn his lines in English [….] And for the most part, maybe because he didn’t learn his lines, he just moved his lips’. Baal reflects on one specific sequence, a love scene between Herta and Enrico, and reveals that she was met on set by a bottle of whisky, ‘schmaltzy’ music, red lights and a number of photographers who were clearly expecting some nudity from the actress; Baal demanded that the music and the lights be turned off, and the whisky and photographers taken from the room. Baal suggests that the film was ‘badly written’ and ‘exceptionally long’, and that in fact she ‘nodded off’ midway through her viewing of the picture. This interview is in German, with optional English subtitles. Baal talks about how she came to be involved in Solange. Her initial response to the script was to tell Dallamano that the picture ‘could easily be made into a porn movie’, so she amended her contract to assert that she will not appear naked in the film and will not be associated with any of the pornographic scenes; she was convinced to make the picture owing to Fuchsberger’s involvement, and came to realise that the picture ‘wasn’t exactly porn, but it was so squalid’. The film ‘is set in a school where the teachers look like pickpockets and small-time crooks’, Baal asserts, highlighting in particular the sequence in which one of the teachers spies on the girls in the communal shower and ‘All you could see were black triangles and tits, no faces’. Baal is heavily critical, as is suggested from these comments, about the ‘sleazy’ aspects of the picture. She reveals that Fuchsberger shot his lines in English, whilst many of the other actors spoke their own languages on set. Testi, Baal suggests, ‘didn’t learn his lines in English [….] And for the most part, maybe because he didn’t learn his lines, he just moved his lips’. Baal reflects on one specific sequence, a love scene between Herta and Enrico, and reveals that she was met on set by a bottle of whisky, ‘schmaltzy’ music, red lights and a number of photographers who were clearly expecting some nudity from the actress; Baal demanded that the music and the lights be turned off, and the whisky and photographers taken from the room. Baal suggests that the film was ‘badly written’ and ‘exceptionally long’, and that in fact she ‘nodded off’ midway through her viewing of the picture. This interview is in German, with optional English subtitles.

- a new featurette, ‘Innocence Lost’ (29:00). Here, Michael Mackenzie discusses Dallamano’s loose ‘schoolgirl’ trilogy of films. This ‘video essay’ is niftily-edited, illustrated with clips from a number of films, including Fulci’s Non si sevizia un paperino, Argento’s Profondo rosso (Deep Red, 1975), Lado’s Chi l’ha vista morire?, and the three ‘schoolgirl in peril’ films with which Dallamano was associated. It discusses Dallamano’s work as a cinematographer and his early career as a director, including his directorial debut, the thrilling all’italiana film La morte non ha sesso (A Black Veil for Lisa, 1968). Mackenzie situates Solange within Italian cinema’s depiction of childhood more generally, in the work of both Italian ‘art’ cinema filmmakers, and suggests that children tend to be absent from the more popular forms within Italian cinema, including the thrilling all’italiana. The figure of the ‘killer priest’ within the thrilling subgenre is discussed, alongside the thrilling’s approach towards the church more generally. Solange, in particular, highlights ‘the gulf’ that exists between how the schoolgirls are perceived by authority figures within the film and how they behave amongst themselves. Mackenzie engages with the film’s depiction of the young women contained within them, and its mealy-mouthed exploitation of their sexuality whilst at the same time criticising the male characters’ expoitation of these adolescents. - the film’s trailer (3:05). The release also comes with reversible artwork and a handsome booklet. The booklet, illustrated handsomely with promotional artwork and stills from the film, contains information about the restoration alongside a new piece about Morricone’s score by Howard Hughes, and an article about Camille Keaton’s career by Art Ettinger.

Overall

Solange is an interesting film, despite Baal’s criticisms of it in her interview that’s included on this disc. The picture draws upon the ‘wrong man’ narrative associated with Hitchcock’s films, as do many of the thrilling all’italiana films of the period in which Solange was made, and its depiction of the schoolgirls’ secret society connects it with the Edgar Wallace krimi pictures (alongside its London setting and the presence of Baal and Fuchsberger). It’s strangely incoherent, in the sense that it seems to criticise what it also revels in. This is perhaps most firmly emphasised in the film’s depiction of the teacher who spies voyeuristically on the schoolgirls whilst they shower. As he walks away, wiping spittle away from his mouth and with a stoned look on his face, the viewer is clearly intended to look upon his character critically; however, as he spies on the girls, the camera shares his gaze, not shying away from depicting the girls’ nudity graphically, reducing the young women – in Baal’s words – to ‘black triangles and tits, no faces’. (It’s perhaps worth noting that the staging of this shower scene may very well have been an influence on the shower scene that opens Brian De Palma’s 1976 adaptation of Stephen King’s novel Carrie.) On the other hand, some elements of the film – for example, its cognisance of how young women are conditioned into certain stereotypical behaviours and exploited by men – could be seen as offering a crypto-feminist statement. Solange is an interesting film, despite Baal’s criticisms of it in her interview that’s included on this disc. The picture draws upon the ‘wrong man’ narrative associated with Hitchcock’s films, as do many of the thrilling all’italiana films of the period in which Solange was made, and its depiction of the schoolgirls’ secret society connects it with the Edgar Wallace krimi pictures (alongside its London setting and the presence of Baal and Fuchsberger). It’s strangely incoherent, in the sense that it seems to criticise what it also revels in. This is perhaps most firmly emphasised in the film’s depiction of the teacher who spies voyeuristically on the schoolgirls whilst they shower. As he walks away, wiping spittle away from his mouth and with a stoned look on his face, the viewer is clearly intended to look upon his character critically; however, as he spies on the girls, the camera shares his gaze, not shying away from depicting the girls’ nudity graphically, reducing the young women – in Baal’s words – to ‘black triangles and tits, no faces’. (It’s perhaps worth noting that the staging of this shower scene may very well have been an influence on the shower scene that opens Brian De Palma’s 1976 adaptation of Stephen King’s novel Carrie.) On the other hand, some elements of the film – for example, its cognisance of how young women are conditioned into certain stereotypical behaviours and exploited by men – could be seen as offering a crypto-feminist statement.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release of the film is very good indeed, anchored by the impressive presentation which is easily an improvement over the film’s previous DVD releases. This main presentation is supported with some excellent contextual material. Fans of Italian thrillers will find this to be an essential purchase. References: Dyer, Richard, 2015: Lethal Repetition: Serial Killing in European Cinema. London: British Film Institute Koven, Mikel J, 2006: La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Maryland: Scarecrow Press O’Brien, Shelley F, 2011: ‘Killer Priests: The Last Taboo?’ In: Hansen, Regina (ed), 2011: Roman Catholicism in Fantastic Film: Essays on Belief, Spectacle, Ritual and Imagery. London: McFarland and Company: 256-67 Odell, Colin & LeBlanc, Michelle, 2010: Horror Films. Manchester: Kamera Books Shipka, Danny, 2011: Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980. London: McFarland. Visual Comparison with EC Entertainment DVD release. EC Entertainment DVD:

Arrow’s new Blu-ray:

EC Entertainment DVD:

Arrow’s new Blu-ray:

EC Entertainment DVD:

Arrow’s new Blu-ray:

EC Entertainment DVD:

Arrow’s new Blu-ray:

Miscellaneous grabs from Arrow’s new Blu-ray:

|

|||||

|